How to talk to kids about video games

Dr. Naomi Fisher is a U.K.-based clinical psychologist specializing in trauma and autism. She’s the author of “Changing Our Minds: How Children Can Take Control of Their Own Learning.” Her writing has also appeared in the British Psychological Society’s The Psychologist, among other publications. You can follow her on Twitter. Photo: Justine Diamond

I spend a lot of time talking to parents about screens. Most of those conversations are about fear.

“I’m so worried about my child withdrawing into screens,” they say. “Are they addicted? How can I get them to stop?”

I understand where they are coming from. I’m a clinical psychologist with 16 years of experience working in the U.K. and France, including for the U.K. National Health Service and in private practice. I’m also the mother of an 11-year-old girl and a teenage boy.

“Screen time” has become one of the bogeymen of our age. We blame screens for our children’s unhappiness, anger or lack of engagement. We worry about screen time incessantly, so much so that sometimes it seems that the benchmark of a good parent in 2022 is the strictness of your screen time limits.

Defining screen time

The oddest thing about this is that “screen time” doesn’t really exist. You can’t pin it down unless you think that the screen itself – a sheet of glass – has a magical, harmful effect. A screen is merely a portal to many activities that also happen offline. These include gaming, chatting, reading, writing, watching documentaries, coding, learning languages and art – I could go on.

Just yesterday, my teenager and I played the online word puzzle Redactle together. We’ve been doing it daily for months, and we’ve learned about history, science, poetry and bed bugs along the way. Do word puzzles become damaging because they are accessed via a sheet of glass?

Still, parents are afraid of “too much” screen time, and they want firm answers. “Is 30 minutes a day too much?” they ask. When in turn I ask them what their children are doing on screens, they rarely have much idea. “Watching rubbish” or “wasting time” are common responses. It’s not often that parents spend time on screens with their children, many of them saying that they don’t want to encourage it.

Stop counting the minutes

I tell parents to stop counting the minutes for a moment, and instead spend some time watching their children without judgment. They return surprised.

Parents see their children socializing with friends as they play. They’re designing their own mini-games, or memorizing the countries of the world. They’ve built the Titanic in Minecraft. The “screen time bogeyman” starts to melt away.

For me, screens give families an opportunity.

Photo: Lauren Psyk

They are a chance to connect with our children by doing something they love. And for some young people, there are benefits that they can’t find elsewhere.

Some children I meet don’t feel competent elsewhere in their lives, but feel good about themselves when they play video games. They tell me about Plants vs. Zombies and they come alive. We exchange tips on our favorite way to defend the house from marauding zombies. They love games, but everyone is telling them that they should be doing something else. Often, no other adult seems interested.

I see young people who are really isolated. They have difficulties making friends, or they have been bullied at school. Online gaming can be their first step towards making connections. They don’t have to start with talking: They type on the in-game chat and when they feel ready, move onto voice chat. They emerge in their own time.

Some of the young people I work with have difficulty keeping calm throughout the day. For them, their devices provide a way to take up space. They put on their headphones and sink into a familiar game. They recharge, letting them cope with their day for a bit longer. It’s a wonderfully portable way to decompress.

Do games cause unhappiness?

I’m not saying that there’s never a reason to worry. I meet some young people who are very unhappy. They use gaming to avoid their thoughts and feelings, and they get very angry when asked to stop. The adults around them usually blame the games for their unhappiness, thinking that banning them would help improve their well-being.

But here’s the issue: Gaming is rarely the cause of the problem. Instead, it’s a solution that a young person has found to cope with the way they are feeling. Sometimes, gaming can seem like the only thing that makes them happy. Banning video games takes that away, causing a child to feel angry with their parents at the same time.

We need to address the root of their unhappiness rather than ban something they love, and we need to nurture that relationship. Sometimes, dropping the judgment around gaming can lead to parents and children reconnecting rather than fighting.

Valuing our children’s interests

Appreciating our children’s love of screens is far more than just showing an interest in what they do. When they were little, we looked after their most precious toys, even if they were ragged and dirty. They were important because they were important to our child. We didn’t tell them that their teddy bears were rubbish and we’d like to get rid of them (even if we secretly thought exactly that), because we knew that would hurt them.

Now they’re older, games and digital creations have replaced stuffed toys. When we demonize screens, we demonize the things our children love. We tell them that the things they value aren’t valuable. We tell them the things they enjoy most are a waste of time. That is never going to be a good way to build a strong and supportive relationship.

Instead, I encourage parents to join their kids. Gaming might bore you, but you can be interested in your child and what makes them come alive. You can value their joy, their curiosity and their exploration. You can give the games a go and see what they find so enthralling. Download Brawl Stars, Minecraft or Roblox, and see if your child will show you how to play. If they don’t want to, find a tutorial video for yourself.

Let them see that you are interested in their passions, because you are interested in them. They will see that you value them for who they are. And from that seed, many good things can grow.

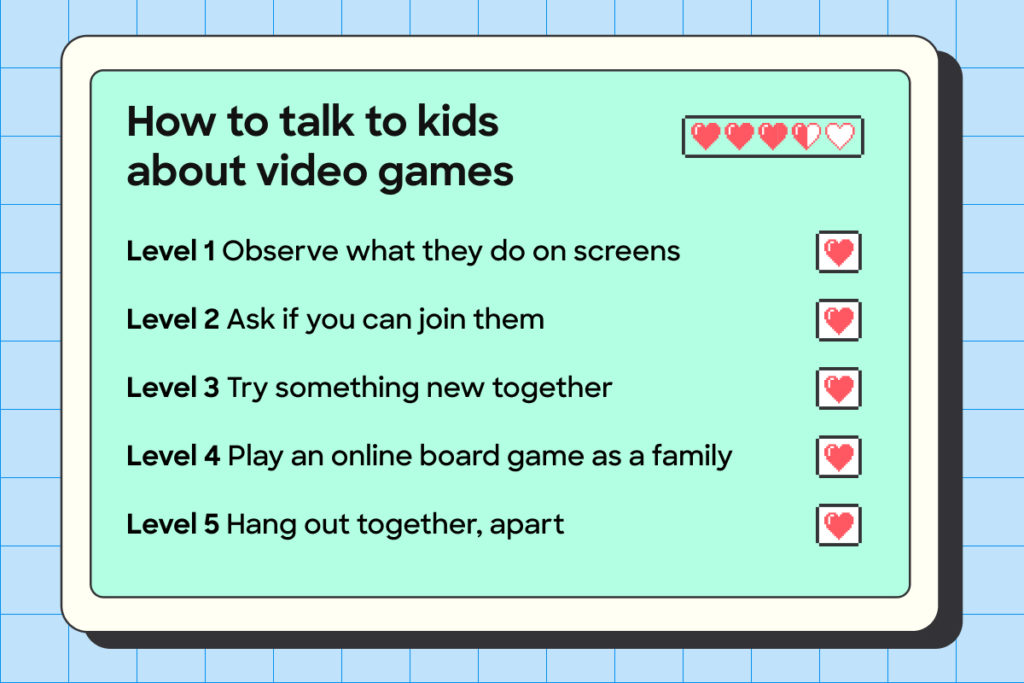

How to talk to kids about video games

![]() Watch what your kids do on screens, even if at first you don’t see the point. Ask them to tell you about it or just observe.

Watch what your kids do on screens, even if at first you don’t see the point. Ask them to tell you about it or just observe.

![]() Ask if you can join them, even if that means watching videos together. Resist the urge to denigrate what they are doing. Search for more websites similar to those they find interesting.

Ask if you can join them, even if that means watching videos together. Resist the urge to denigrate what they are doing. Search for more websites similar to those they find interesting.

![]() Try something different together. Make suggestions and expand their on-screen horizons. There are quizzes galore on Sporcle, or clever spin-offs from Wordle like Quordle, Absurdle and Fibble.

Try something different together. Make suggestions and expand their on-screen horizons. There are quizzes galore on Sporcle, or clever spin-offs from Wordle like Quordle, Absurdle and Fibble.

![]() Connect over a board game. Many family board games have virtual editions. Our family loves the Evolution app. Try Carcassonne, Forbidden Island, Settlers of Catan, or the Game of Life.

Connect over a board game. Many family board games have virtual editions. Our family loves the Evolution app. Try Carcassonne, Forbidden Island, Settlers of Catan, or the Game of Life.

![]() Hang out together, apart. Online gaming can be a great way to spend time with your kids when you aren’t with them. Kids can struggle to talk remotely but playing Minecraft or Cluedo together can be lots of fun, even miles apart.

Hang out together, apart. Online gaming can be a great way to spend time with your kids when you aren’t with them. Kids can struggle to talk remotely but playing Minecraft or Cluedo together can be lots of fun, even miles apart.

The internet is a great place for families. It gives us new opportunities to discover the world, connect with others and just generally make our lives easier and more colorful. But it also comes with new challenges and complications for the people raising the next generations. Mozilla wants to help families make the best online decisions, whatever that looks like, with our latest series, The Tech Talk.