The need for equitable broadband internet access has been a problem since the term “digital divide” was first coined in the mid-1990s, but these conversations are getting renewed attention as a result of COVID-19 forcing lives online more rapidly in 2020 than ever before. At Mozilla, we are committed to building an internet that includes all people and believes that someone’s demographics should not determine their access, opportunities, or quality of experience. Here we explore the digital divide in one of the United State’s most impacted cities — Detroit, Michigan.

It’s been 13 months since the global COVID-19 pandemic hit America. The result, nationwide shutdowns and a country mourning the loss of more than 550K Americans that have died due to COVID-19.

For many upper and middle-class Americans, the ever-extending quarantine has meant a slight adaptation, or even a respite, from past routines as they largely shifted to working from home. It has meant signing on to their laptops every day at home while they invested in ring lights and headphones for the optimal Zoom experience. For those with kids, simultaneously juggling work and their children’s Zoom classes has created a new set of challenges to maintain some semblance of normalcy.

But for millions of others, the pandemic has meant additional uncertainty. Tens of millions of adults remain out of work. Minority communities and urban centers have been disproportionately affected by not only unemployment, sickness and death, but another systematic inequity: lack of high-speed internet access. It has prohibited tens of thousands of students, and their parents, from making the transition from classrooms and workplaces to video-everything.

In other words, the digital divide has become a chasm.

What is the digital divide?

The digital divide has been described as a “disconnect” between those who have access to computers and the internet and those who do not. But experts clarify by saying it is not simply a “disconnect,” it is a “gulf.” It is a distance that is becoming increasingly insurmountable and continues to grow as broadband internet access impacts educational attainment and income.

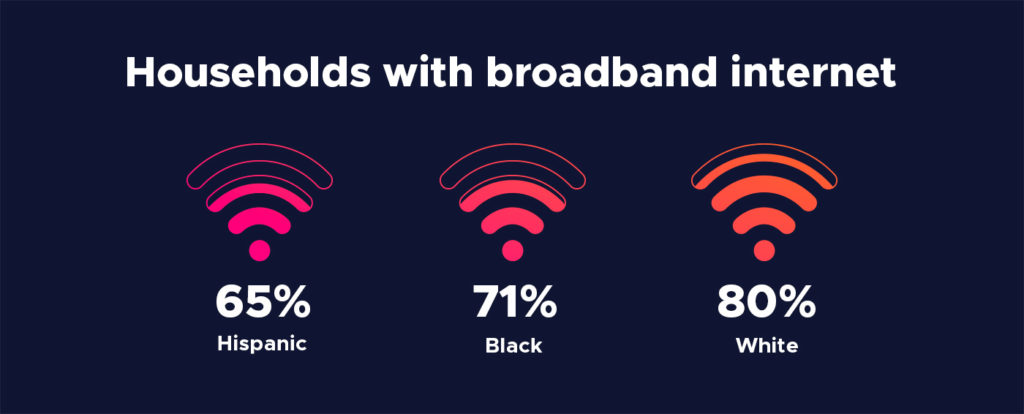

There are two large factors when it comes to the digital divide, income and race — two statistics that are still troublingly intersected. If you are Black or Brown and make less than $30,000 a year, you are significantly less likely to have broadband internet access in your home.

According to the Pew Research Center, in February 2019, 92% of households with an income of $75,000 or greater had reliable high-speed internet access, compared to only 56% of households earning $30,000 or less. And the same study, updated to look at 2020, showed that 80% of white households had broadband internet, compared to 71% of Black households and 65% of Hispanic households. Additionally, while the average American household has 11 devices hooked up to the internet, there are still one in five Americans who can only access the internet via their smartphones.

That means for many Americans, particularly Black and Brown people, the lack of reliable internet service has meant that quarantine life, no matter how long it has lasted, has been incredibly difficult.

What is happening in Detroit?

The median U.S. income prior to the pandemic was $68,703 — pretty close to that $75,000 threshold where 92% of people have broadband internet access. However, in my hometown of Detroit, the median income was only $30,894 going into 2020. Based on these numbers, it should come as no surprise that Detroit is one of the cities with the largest digital divides in the nation. In 2019, 35.6% of Detroit households did not have broadband internet. In response, the city hired Joshua Edmonds as Detroit’s first municipal Director of Digital Inclusion. His job is to help build a city-wide strategy to combat this gap.

Edmonds explained his role saying, “Detroit doesn’t have the luxury of maintaining the status quo. We get tagged as innovative for things that are, honestly, utterly necessary.”

In his role, Edmonds works to expand technology in the community by leveraging relationships with community partners, neighborhoods, schools and for-profit companies. While he has previously faced roadblocks in Washington, D.C., he is still optimistic.

“In rural America, the FCC, USDA, they have clear-cut federal funding, recommendations, mandates, and states allocating resources. For a long time, the same wasn’t true for urban centers,” Edmonds says. “The Rural Opportunity Fund has $16 billion that they’re allocating already on top of more aid that’s coming.”

However, the lockdown of the last year has put the lack of broadband internet access in urban centers, like Detroit, in the spotlight. Senators like Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn, have spoken out about the digital divide. And in March, President Joe Biden included broadband internet access in his $2 trillion American Jobs Plan infrastructure proposal. After President Biden’s announcement, Jessica Rosenworcel, the acting chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), was quick to respond in support on Twitter.

Broadband for 100% of us. I'm all in.

— Jessica Rosenworcel (@JRosenworcel) March 31, 2021

None of these solutions will be enough though unless there is an understanding of how intertwined race and internet access are and we reduce barriers to access. This is especially of concern for Detroit as one of the most segregated cities in America. The city is more than 80% Black and Hispanic. In southwest Detroit, which is almost entirely Hispanic, gaining internet access for citizens has even more barriers.

One barrier is language, but according to Nyasia Valdez, Digital Stewards Trainer for the Equitable Internet Initiative and a lifelong resident of southwest Detroit, most of the connectivity challenges in her neighborhood are rooted in poverty.

While many southwest Detroit residents qualify for low-income internet access, the neighborhood’s two internet service providers, Comcast and AT&T, have extensive proof of residency requirements, especially in homes that have a previous balance. You have to go to the official office during working hours, which is already difficult for people with jobs that do not provide paid time off. Then there is very specific documentation you have to bring with you, not only official proof of current residency but also proof of past residency to prove you were not living in the home when the previous debt was incurred. Finally, proof of SNAP benefits is required for eligibility.

Valdez has seen such a dramatic increase in the need for low-income internet support during the pandemic. In response, her organization set up stopgap public wifi hotspots for citizens who could not obtain internet services in their homes, which allows for kids to go to neighborhood parks and do homework in cars.

“They were meant to buy us some time until we can build more infrastructure in the community,” Valdez says.

Edmonds believes that high-speed internet access is necessary for connectivity to crucial social infrastructures like medical providers, educational institutions and employment. It seems impossible to close the wealth gap without abolishing the digital divide.

“In Detroit, about 40% of residents don’t have internet access,” Edmonds says. “So you have a splintered lifeline, and it, therefore, affects everything else. If we can mitigate the internet connectivity issue, the splintered lifeline, then we would be mitigating impact in every other area imaginable from small businesses to healthcare delivery, to learning, to employment, to well-being.”

What are the next steps?

Similar digital divides are found across the country and globally. Detroit is just a microcosm of a larger problem across the nation. In March, Tim Berners-Lee, credited as the creator of the World Wide Web, warned of the widening digital divide and declared that internet connectivity should be a basic right. The $100 billion set aside in the American Jobs Plan infrastructure proposal for digital infrastructure is a good first step, coupled with the FCC’s Emergency Broadband Internet that was implemented in February 2021 to give a monthly discount on broadband service to low-income households. But it is not nearly enough.

The Washington Post editorial board argued that the allocation of funds to support broadband connectivity in the country should have been around $50 billion to address the “twin challenges” of the availability of broadband and its affordability.

But as more of our lives migrate online, the finish line changes. In fact, In 2020, EducationSuperHighway completed its mission of upgrading the internet access in every public school classroom in America. The organization was ready to “sunset” by August 2020 — a term that means shutting down a non-profit program that had met its goals. Then COVID-19 hit. In May 2020, the organization announced they were delaying their sunset in order to focus on outside-the-classroom connectivity for the estimated 7-12 million students who lack access at home. In the remote school environment, EducationSuperHighway’s previous work to provide broadband internet at schools was no longer enough to close the gap due to lack of internet access at home, as well as device accessibility.

Edmonds believes that the coronavirus pandemic has given Americans the opportunity to recognize that the need for equitable internet access is urgent and affects us all. While implementation was the goal for 2020, for Edmonds, 2021 is all about “fine-tuning.”

People can come together to work on this by putting pressure on large providers to reduce the requirements for access, partner with our local governments to find out what is happening in their own backyards, and educating themselves on the current administration’s infrastructure plan, The American Jobs Plan.

“Let’s focus on marketing and branding, let’s focus on a city-wide network, let’s get kids excited and trained to take their internet skills to new levels,” he says, excitedly. “And for those who aren’t connected, let’s raise more money and make that happen, and for the households that are newly connected, let’s take their usage to new levels in banking, telehealth, education.”

The challenge of fair, affordable, and equitable internet access is one that America can rise to meet.

“If it’s one thing this pandemic has shown us all,” Edmonds says, “is that when we really try, Americans can mobilize and achieve great things.”