Here’s a surprising fact: It costs money to watch video online, even on free sites like YouTube. That’s because about 4 in 5 videos on the web today rely on a patented technology called the H.264 video codec.

A codec is a piece of software that shrinks large media files so they can travel quickly over the internet. In browsers, codecs decode video files so we can play them on our phones, tablets, computers, and TVs. As web users, we take this performance for granted. But the truth is, companies pay millions of dollars each year to bring us free video – and the bills are only going to get bigger.

Today most video files can play on most devices, thanks to the ubiquity of H.264. How might this situation change? Let’s start with some facts and factors that govern the big business of web video.

Streaming video costs (a lot of) money. A lot of companies pay a lot of money to use H.264. They include software and networking companies; content creators and distributors like Netflix, Amazon, and YouTube; and chip manufacturers like ARM. Where does the money go? To MPEG-LA, which represents tech innovators in the U.S., Japan, South Korea, Germany, France, and Holland.

Newer codecs are twice as efficient. In the business world, efficiency equals money. Better compression opens the door to two key business benefits: better video quality and lower bandwidth costs. Companies like Cisco, YouTube, and Netflix pay massive networking bills to send video files to your browser. Today, more than 70% of all internet traffic is video, and that percentage is predicted to top 80% in the next few years.

New codecs may cost ten times more. MPEG-LA’s next-generation HEVC/H.265 is more efficient than H.264. The downside is, it carries 23 patents and remarkably confusing terms, originally created for DVD players. Early estimates show licensing fees for H.265 could cost ten times more than today’s H.264. Who will absorb those costs? How much will companies like Netflix have to pass on in fee hikes to stay profitable?

With H.264, small players get a free ride. To help build momentum for the H.264 codec, Cisco announced in 2013 it would open-source H.264. Cisco offered H.264 binaries to developers free of charge, so small shops could add streaming functionality to their applications. Mozilla uses Cisco’s OpenH264 in Firefox. If not for Cisco’s generosity, Mozilla would be paying estimated licensing fees of $9.75 million a year. Now the question is: Will Cisco cover licensing fees for HEVC/H.265 as well? If not, what impact will royalties have on web development? How will startups, hobbyists, and open source projects get access to this crucial web technology?

A drive to create royalty-free codecs

Mozilla is driven by a mission to make the web platform more capable, safe, and performant for all users. With that in mind, the company has been supporting work at the Xiph.org Foundation to create royalty-free codecs that anyone can use to compress and decode media files in hardware, software, and web pages.

But when it comes to video codecs, Xiph.org Foundation isn’t the only game in town.

Over the last decade, several companies started building viable alternatives to patented video codecs. Mozilla worked on the Daala Project, Google released VP9, and Cisco created Thor for low-complexity videoconferencing. All these efforts had the same goal: to create a next-generation video compression technology that would make sharing high-quality video over the internet faster, more reliable, and less expensive.

In 2015, Mozilla, Google, Cisco, and others joined with Amazon and Netflix and hardware vendors AMD, ARM, Intel, and NVIDIA to form AOMedia. As AOMedia grew, efforts to create an open video format coalesced around a new codec: AV1. AV1 is based largely on Google’s VP9 code and incorporates tools and technologies from Daala, Thor, and VP10.

Why Mozilla loves AV1

Mozilla loves AV1 for two reasons: AV1 is royalty-free, so anyone can use it free of charge. Software companies can use it to build video streaming into their applications. Web developers can build their own video players for their sites. It can open up business opportunities, and remove barriers to entry for entrepreneurs, artists, and regular people. Most importantly, a royalty-free codec can help keep high-quality video affordable for everyone.

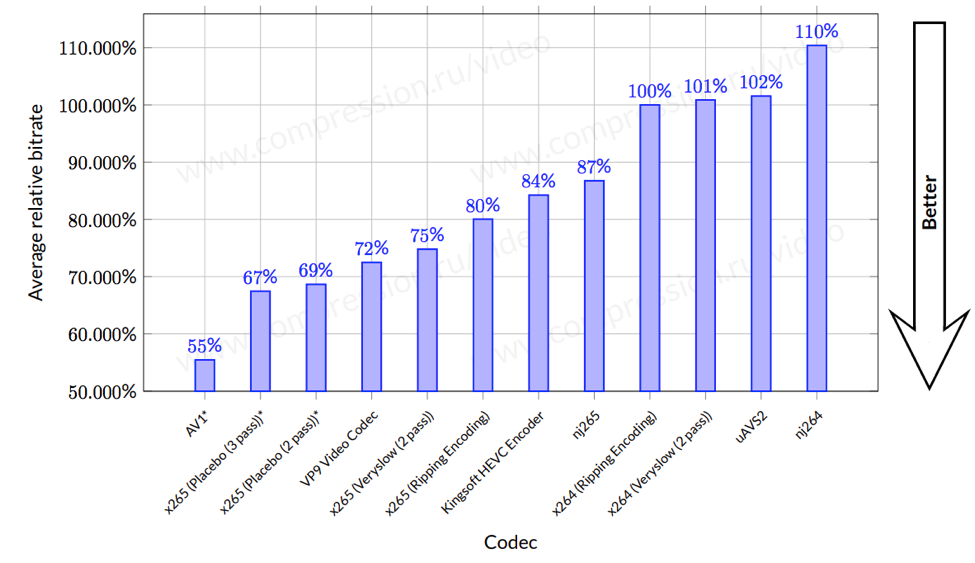

The second reason we love AV1 is that it delivers better compression technology than even high-efficiency codecs – about 30% better, according to a Moscow State University study and testing at Facebook. For companies, that translates to smaller video files that are faster and cheaper to transmit and take up less storage space in their data centers. For the rest of us, we’ll have access to gorgeous, high-definition video through the sites and services we already know and love.

Open source, all the way down

AV1 is well on its way to becoming a viable alternative to patented video codecs. As of June 2018, the AV1 1.0 specification is stable and available for public use on a royalty-free basis. Looking for a deep dive into the specific technologies that made the leap from Daala to AV1? Check out our Hacks post, AV1: next generation video – The Constrained Directional Enhancement Filter.