In 1981, the GDR also conducted a census – albeit without protest. The people of East Germany had to assume either way that the state was fully informed about them, because the population was well aware of the fact that the Ministry of State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, MfS) was keeping files on deviant behaviour. Here, too, what played a major role was the fact that the GDR, like the Federal Republic of Germany, had been in a position to compare individual data records with others since the late 1960s.

One of the companies that turned the protection of privacy in the GDR into a question of computers in society was the Robotron Combine. With a staff of seventy thousand, it had as many employees in the 1980s as Google has today and was by far the largest company in the GDR. The technology for computer construction was bought, copied and stolen by the GDR from companies in France, the USA and West Germany.

The surveillance pattern and the level of detail of the files enjoyed a mythical reputation among the population and abroad, which was mainly due to the fact the secret service had managed to successfully carry out some spectacular espionage coups and attacks in the West –especially the one that led to the toppling of German West German Chancellor Willy Brandt.

In contrast to most Western secret services, the MfS was also responsible for defending the state against internal enemies and prepared files for twenty-five percent of its own population. By the end of the GDR, two hundred kilometres of shelving had been accumulated, which seems like a drop in the ocean in comparison to the data volumes handled by intelligence services today.

It was only after 1990 that those affected were able to get an idea of the poor quality of data recorded. The GDR’s surveillance regime was an incredible waste of resources. Agents tracked innocent students, noted when the “target” turned off the lights in the evening, waited all night in the car outside their house and noted at what time the lights came back on in the morning.

By its very nature, a service which draws its reputation and self-image from the size of a potential threat, will make that threat appear ever larger and eventually going mad and losing control of its own operations. It was becoming increasingly difficult for the Ministry to tolerate hideaways and retreats where people could do whatever they wanted. Uncontrolled privacy almost caused Erich Mielke, Head of the MfS from 1957 to 1989, physical pain. “Who is who?”, he philosophised before his officials, “If we knew that, comrades, we wouldn’t be doing all this.”

Can privacy be controlled?

Although the MfS, just like the West German Federal Police, managed to construct metadata from its banal spy reports and to identify social networks of monitored persons, the East German secret service was not so much a threat because of the data it held, but rather because of its high criminal energy and the social damage it caused by destroying privacy in the GDR.

The MfS in the GDR did exactly what the West German Constitutional Court had only described in its census verdict as a mere scenario: the state gave its citizens the impression that they were constantly being observed and assessed. By rewarding compliant behaviour and customised CVs, it ended up digging its own grave.

The gravely wrong political experiment involving seventeen million inhabitants was bound to fail because the system was based on two gross misjudgements of the security regime: first, it believed it could control the interaction between privacy and society; second, it ignored the fact that privacy is the key driver of social progress and innovation.

After all, there were many people for whom privacy is essential and who defend their privacy fiercely. The more the state tries to invade this sphere, the greater the resistance. The MfS forcibly expelled civil rights activist Jürgen Fuchs from university although he was a brilliant student. It threatened and tortured him, exposed him to dangerous levels of radiation (Fuchs died of cancer at the age of 48) and finally deported him to West Germany. In 1986, the MfS carried out a bomb attack in front of his house in West Berlin, because Fuchs simply would not stop criticising the GDR.

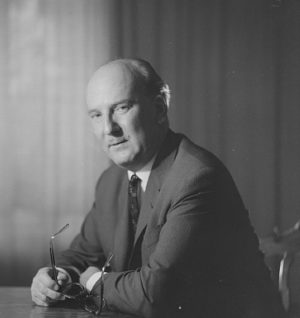

The physicist Werner Hartmann was one of the most important and innovative German researchers of the post-war period. He had already presented a one thousand-line TV screen in 1938, was forcibly redeployed by the Nazis to develop weapons and was deported by the Soviets in 1945 where he was forced to conduct war research for the “other side”. In 1955, he received permission to return to the GDR, where he founded the Centre for Molecular Electronics in 1961 and therefore briefly connected the GDR to Western computer technology.

However, he did not succeed in securing political support for his work and naïvely believed that he could earn freedom through performance. That was the worst of all attitudes one could adopt towards the MfS. So, Hartmann was soon regarded as someone who “dared to put the fundamental laws of physics above the official political line of the party”.

The MfS restricted his freedom to travel and broke up his marriage. It systematically spied on his private life for twenty years, but never found any tangible evidence of political renegade. Hartmann was simply apolitical, which had not been envisioned in the MfS’s system. When one of his closest associates tried to flee to the West, the trap slammed shut.

The MfS accused Hartmann of complicity and the former employee was imprisoned for fifteen years. Hartmann was initially suspended and then dismissed from his post. He was accused of having a “bourgeois, anti-communist and anti-Soviet attitude”. His salary was reduced by eighty-four percent, he lost all social ties and was no longer allowed to conduct research in the GDR. Suffering from severe depression, which could of course not be treated in the GDR, he spent the rest of his life until his death in 1988 on his bed staring at the ceiling.

Can there be progress without privacy?

Anyone who came under the investigators’ scrutiny basically had only the choice of surviving the fight until the very end and saving their honour by exposing almost all social relations. Otherwise, they would suffer brutal social isolation like Hartmann. By destroying privacy, the GDR also destroyed the innovative power of the state, although the GDR was much more dependent on individual personalities such as Hartmann than Western states.

After all, in communist Eastern Europe, innovation could only take place within state-controlled institutions. A start-up in somebody’s private garage, as in 1970s Silicon Valley, was simply inconceivable in the GDR because the state would have immediately classified such garages as uncontrollable and subversive and razed them to the ground.

With its fight against privacy, the GDR excluded itself from the international innovation cycle, because innovation comes from the flow of information and originates from freedom of movement. But those who are free to roam can also stay informed. This was something the GDR could not afford to allow.

The level of secrecy for everything continued to increase until the collapse of the GDR. Initially, this was because of fears that enemy countries would copy technical innovations, but ultimately it was out of increasing desperation because people were not supposed to know how far the GDR was lagging behind Western states in terms of development.

Are citizens allowed to know what the state knows?

Not only was the personal information of its citizens unprotected in the GDR, but it was even to be explicitly collected and evaluated. Data protection as we know it today did not exist in the GDR. However, there was “data security”, which meant that the state monopolised the possession of data and shielded it from third parties. What is more, the government’s neurosis meant that, essentially, only the MfS had unrestricted access to the data of the public.

Other authorities were only allowed to link a limited number of databases. Because in a country where housing shortages were the central social problem, municipalities could not be allowed to compare population data with housing policy data. Otherwise, it would have been noted for example, that many apartments were underused because the MfS was maintaining “conspiratorial rooms”.

All this led to the emotions running high at the end of the GDR. On 15 January 1990, angry citizens stormed and occupied MfS buildings all over the GDR. However, MfS employees had already begun to destroy sensitive files. Both say much about how much the awareness of justice and injustice among the public and among the approximately 90,000 MfS employees was still intact, even after four decades of dictatorship.

The exact extent of the data loss caused by MfS destruction is still unclear. The surviving records, however, now entered a different cultural context and are a prime example of how unpleasant it is when private, sometimes intimate, conversations and remarks are made public. The most prominent example of this is former Chancellor Helmut Kohl.

The MfS had managed to intercept and record telephone calls and conversations of the chancellor. When Kohl learned about the existence of these records around the turn of the millennium, he immediately took his case to the Berlin Administrative Court to prevent journalists, historians or politicians from reading his file. Ironically, he was appealing against a law the Federal Government had introduced under his leadership as Chancellor in 1991…and he won.

The court classified his personal rights above the public interest and spared Kohl the humiliation Richard Nixon or Henry Kissinger had to endure after the publication of the so-called “Nixon Tapes”: the humiliation of their personalities down to a normal level.

However, there was a catch because news of the files’ existence had been announced in the middle of a trial concerning illegal donations to Kohl’s party (CDU) and many expected clues from these. Some would also have liked to know why media giant Leo Kirch had transferred DM 600,000 to the Chancellor. But that is another story.

This was the state of awareness with which reunified Germany entered the digital age. The collection and storage of personal information as well as data protection were first and foremost a government matter. At the turn of the millennium, there was not a single German company that had more data than the state, except for of the semi-public company Deutsche Telekom founded in 1995.

Internet pioneers celebrated the emerging tech companies from the USA with books like “Elites in an Egalitarian World” (Malte Herwig), ““The Liberation of Information” (André Spiegel) or “What Would Google Do?” (Jeff Jarvis). The circulation of daily newspapers was at an all-time high, the most successful social networks for Germans came from Germany and could easily be regulated according to national law – for example, the job market Xing (2003) or the VZ networks.

After twenty years(!) of deliberating, even the European Commission had agreed on a common approach with the catchy title of “Directive 95/46/EC on the protection of individuals regarding the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data”. Everything seemed to be under control; Germany and Europe were prepared for the Internet age – until Google bought web analytics provider Urchin Software.

READ THE SERIES:

<< Part 1: “You have to force them to leave tracks” || Part 3: “Governments will demand that.” >>

This post is also available in: Deutsch (German)