(This begins a two-part series on upcoming changes in Firefox Sync, based on my presentation at RealWorldCrypto 2014. Part 1 is about problems we observed in the old system. Part 2 will be about the system which replaces it.)

In March of 2011, Sync made its debut in Firefox 4.0 (after spending a couple of years as the Weave add-on). Sync is the feature that lets you keep bookmarks, preferences, saved passwords, and other browser data synchronized between all your browsers and devices (home desktop, mobile phone, work computer, etc).

Our goal for Sync was to make it secure and easy to share your browser state among two or more devices. We wanted your data to be encrypted, so that only your own devices could read it. We weren’t satisfied with just encrypting during transmission to our servers (aka “data-in-flight”), or just encrypting it while it was sitting on the server’s hard drives (aka “data-at-rest”). We wanted proper end-to-end encryption, so that even if somebody broke into the servers, or broke SSL, your data would remain secure.

Proper end-to-end encryption typically requires manual key management: you would be responsible for copying a large randomly-generated encryption key (like cs4am-qaudy-u5rps-x/qca-hu63l-8gjkl-28tky-6whlt-fn0) from your first device to the others. You could make this easier by using a password instead, but that ease-of-use comes at a cost: short, easy-to-remember passwords aren’t very secure. If an attacker could guess your password, they could get your data.

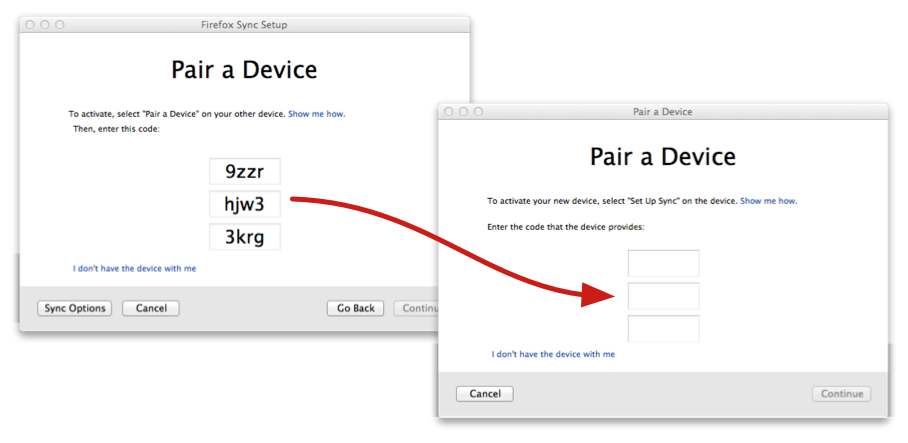

We didn’t like that tradeoff, so we designed an end-to-end encryption system that didn’t use passwords. It worked by “pairing”, which means that every time you add a new device, you have to introduce it to one of your existing devices. For example, you could pair your home computer with your phone, and now both devices could see your Sync data. Then later, you’d pair your phone with your work computer, and now all three devices could synchronize together.

The introduction process worked by copying a short single-use “pairing code” from one device to the other. This code was fed into some crypto magic (the J-PAKE protocol), allowing the two devices to establish a temporary encrypted connection. Then everything necessary to access your account (including the random long-term data-encryption key) was copied through that secure connection to the new device.

The cool thing about pairing is that your data is safely protected by a strong encryption key, against everyone (even the Mozilla server that hosts it), and you don’t need to manage the key. You never even see it.

Problems With Pairing

But, we learned that our pairing implementation had some problems. Some were shallow, others were deep, but the net result is that a lot of people were confused by Sync, and we didn’t get as many people using it as we’d hoped. This post is meant to capture some of the problems that we observed.

Idealized Design vs Actual Implementation

Back in those early days, four years ago now, I was picturing a sort of idealized Sync setup process. In this fantasy world, next to the rainbows and unicorns, the first machine would barely have a setup UI at all, maybe just a single button that said “Enable Sync”. When you turned it on, that device would create an encryption key, and start uploading ciphertext. Then, in the second device, the “Connect To Sync” button would initiate the pairing process. At no point would you need a password or even an account name.

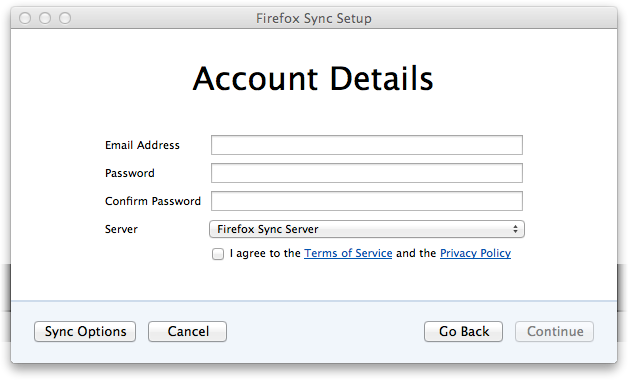

But, for a variety of reasons, by the time we had a working deliverable, our setup page looked like this:

Some of the reasons were laudable: having an email address lets us notify users about problems with their account, and establishing a password enabled things like a “Delete My Account” feature to work. But part of the reason included historical leftovers and backward-compatibility with existing prototypes.

In this system, the email address identified the account, and the password was used in an HTTP Basic Auth header to enable read/write access to encrypted data on the server. The data itself was encrypted with a random key, which came to be known as the “recovery key”. The pairing process copied all three things to the new device.

Deceptive UI

The problem here was that users still had to pick a password. The account-creation screen gave the impression that this password was important, and did nothing to disabuse them of the notion that email+password would be sufficient to access their data later. But the data was encrypted with the (hidden) key, not the password. In fact, this password was never entered again: it was copied to the other devices by pairing, not by typing.

It didn’t help that Firefox Sync came out at about the same time as a number of other products with “Sync” in the name, all of which did use email+password as the complete credentials.

This wasn’t so bad when the user went to set up a second device: they’d encounter the unusual pairing screen, but could follow the instructions and still get the job done. It was most surprising and frustrating for folks who used Firefox Sync with only one device.

“Sync”, not “Backup”

We, too, were surprised that people were using Sync with only one device. After all, it’s obviously not a backup system: given how pairing works, it clearly provides no value unless you’ve got a second device to hold the encryption key when your first device breaks.

At least, it was obvious to me, living in that idealistic world with the rainbows and unicorns. But in the real world, you’d have to read the docs to discover the wonderous joys of “pairing”, and who in the real world ever reads docs?

It turns out that an awful lot of people just went ahead and set up Sync despite having only one device. For a while, the majority of Sync accounts had only one device connected.

And when one of these unlucky folks lost that device or deleted their profile, then wanted to recover their data on a new device, they’d get to the setup box:

and they’d say, “sure, I Have an Account”, and they’d be taken to the pairing-code box:

and then they’d get confused. Remember, for these users, this was the first time they’d ever heard of this “pairing” concept: they were expecting to find a place to type email+password, and instead got this weird code thing. They’d have no idea what those funny letters were, or what they were supposed to do with them. But they were desperate, so they’d keep looking, and would eventually find a way out: the subtle “I don’t have the device with me” link in the bottom left.

Now, this link was intended to be a fallback for the desktop-to-desktop pairing case, where you’re trying to sync two immobile desktop-bound computers together (making it hard to transcribe the pairing code), and involves an extra step: you have to extract the recovery key from the first machine and carry it to the second one. By “I don’t have the device with me”, we meant “another device exists, but it isn’t here right now”. It was never meant to be used very often.

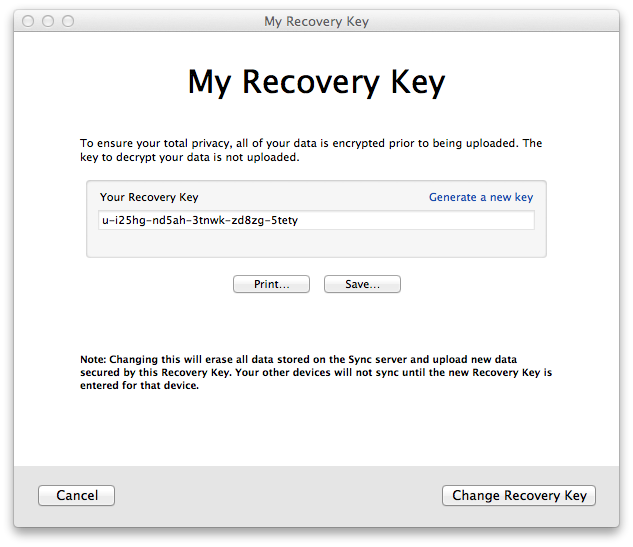

This also provided a safety net: if you had magically known about the recovery key ahead of time, and wrote it down, you could recover your data without an existing device. But since pairing was supposed to be the dominant transfer mechanism, this wasn’t emphasized in the UI, and there were no instructions about this at account setup time.

So when you’ve just lost your phone, or your hard drive got reformatted, it’s not unreasonable to interpret “I don’t have the device with me” as something more like “that device is no longer with us”, as in, “It’s dead, Jim”.

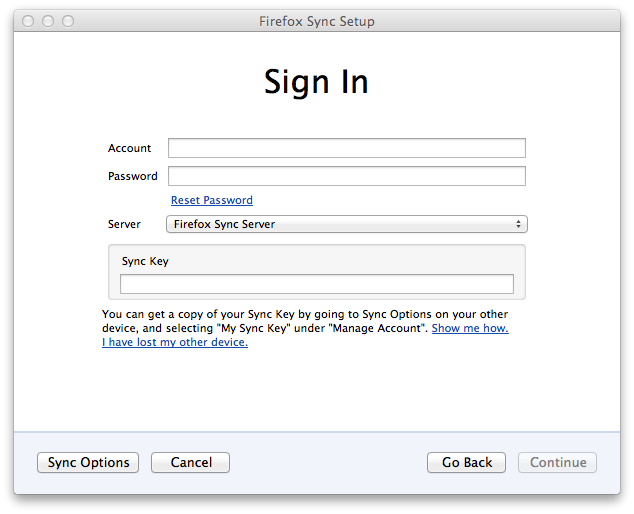

Following the link gets them to the fallback dialog:

Which looked almost like what they were expecting: there’s a place for an account name (email), and for the password that they’ve diligently remembered. But now there’s this “Sync Key” field that they’ve never heard of. The instructions tell them to do something impossible (since “your other device” is broken). A lot of very frustrated people wound up here, and it didn’t provide for their needs in the slightest.

Finally, these poor desperate users would click on the only remaining ray of hope, the “I have lost my other device” link at the bottom. Adding insult to injury, this actually provides instructions to reset the account, regenerate the recovery key, and delete all the server-side data. If you understand pairing, it’s clear why deleting the data is the only remaining option (erase the ciphertext that you can no longer decrypt, and reload from a surviving device). But for most people who got to this point, seeing these instructions only caused even more confusion and anger:

(When reached through the “I have lost my other device” link, this dialog would highlight the “Change Recovery Key” button. This same dialog was reachable through Preferences/Sync, and is how you’d find your Recovery Key and record it for later use.)

User Confusion

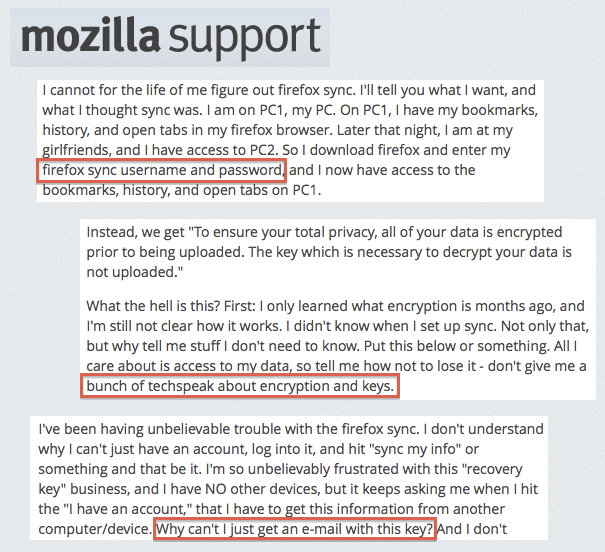

The net result was that a lot of folks just couldn’t use Sync. You can hear the frustration in these quotes from SUMO, the Firefox support site, circa December 2013:

The upshot is that, while we built a multi-device synchronization system with excellent security properties and (ostensibly) no passwords to manage, a lot of people actually wanted a backup system, with an easy way to recover their data even if they’d only had a single device. And they wanted it to look just like the other systems they were familiar with, using email and password for access.

Lessons Learned

We’re moving away from pairing for a while: Firefox 29 will transition to Firefox Accounts (abbreviated “FxA”), in which each account is managed by an email address and a password. Sync will still provide end-to-end encryption, but accessed by a password instead of pairing. My next post will describe the new system in more detail.

But we want to bring back pairing some day. How can we do it better next time? Here are some lessons I’ve learned from the FF 4.0 Sync experience:

- do lots of user testing, early in the design phase

- especially if you’re trying to teach people something new

- pay attention to all the error paths

- if your application behaves differently than the mainstream, make it look different too

- observe how people use your product, figure out what would meet their expectations, and try to build it

- if you think their expectations are “wrong” (i.e. they don’t match your intentions), that’s ok, but now you have two jobs: implementation and education. Factor that into your development budget.

I still believe in building something new when it’s better than the status quo, even if it means you must educate your users. But I guess I appreciate the challenges more now than I did four years ago.

(cross-posted to my personal blog)

I have to agree with the education points in here, I know enough crypto to shoot myself in the foot and it still took me a while to work out what Sync was doing. However, I’d have to say it got better at pointing details over releases; I had to wipe and restart my data a few times and I remember being told to write the recovery key down, but only later on, definitely not at the beginning.

Having said that, I’m really hoping pairing makes a comeback, I liked the ‘2-factor’ with keys under my control idea that it introduced. In fact that’s reason I’m using Sync to store passwords instead of an external manager.

How to synchronize a bluetooth devices, wifi devices, wireless device: type a (displayed) PIN code, or press a sync button.

If you ask for email, it’s not a peer synchro but a cloud synchro, like dropbox, google, microsoft, itunes…

And going from one to another cause confusion.

User aren’t able to remember, they forgot their passwords, even their 4 digit credit card pin code and you can’t blame them, they’re humans.

The only two thing you can rely on is their email address and their ID (if the’ve purchased something): they will understand that if they don’t own their email anymore or can’t give a proof of their ID, it’s their fault.

So if you ask them to keep the recover key, they will fail. The only case where it doesn’t work too bad: the authenticators, because it’s for gamers that will take care of their account because they know the value.

A 8 character password is enough to protect ACCESS because you can ask delay between each try.

Encryption can’t work with passwords because it’s not an access method with delay but data that is protected with encryption algorythms. And that’s more vulnerable to bruteforce, so we use passphrases, keys or private certificates.

You won’t be able to give encryption to user if they can’t manage passphrases, keys or provate certificates.

And they can’t be recovered with email, so they need backup.

Ask a user to be able to consult their email is easy

Ask him to be able to do backups (with coverage, frequency, separation, history, testing, security, integrity) is really hard.

I think the problem was that Sync covered both bookmarks and saved passwords. Encryption is a necessity for saved passwords but many people just wanted to save/sync their bookmarks and for this, full end-to-end encryption requiring a recovery key was an overkill.

With the new Firefox Sync, the user experience has improved, but what we have lost is (1) ability to use our own sync servers (2) protect the sync data even from Mozilla (in case they get hacked).

A possible solution for (2) can be to ask the user to specify their own recovery key instead of deriving it from his password. This should be optional so that majority of the users can continue using the simple password-based sync (trusting Mozilla) while the paranoid ones can use the advanced version by using their own key. The UI should inform them to note down the key. Password would still be required because the data is stored at Mozilla servers but it wouldn’t be possible to decrypt the data merely with the password.

That leaves the problem (1) of ability to use our own sync servers. I don’t know how critical that is.

You can actually still run your own Sync servers. It’s a little bit more involved now (you have to run three servers: fxa-auth-server, tokenserver, sync-storage-server), but it’s still totally possible. We need to set up a blog post describing how to do it, but there may be some discussion on the “services-dev” mailing list that’d be useful.

I’d argue that the new Sync stil protects your data even from a hacked Mozilla server: someone who gets the server’s data, but who can’t guess your password, won’t be able to decrypt your Sync data. It’s now dependent upon the quality of your password, though, so choosing a good one matters more than it did before.

To be precise, the new Sync encryption key is not strictly “derived from” the password, but is instead “wrapped by” the password. You have to combine the wrapped value (stored by the server) with the user’s password (never revealed to the server) to unwrap the encryption key. If we derived the key directly from the user’s password, without additional secrets mixed in, then any storage server would have enough information to attempt a brute-force dictionary attack. By using wrapping instead, only the fxa-auth-server can mount that attack, reducing the size of the security perimeter.

thanks! -Brian

[…] et avec un code de qualité insuffisante, une nouvelle version a été développée. Au lieu du mécanisme de couplage, Sync utilise maintenant une authentification simplifiée basée sur un couple adresse de courriel […]

Awaiting part 2 of this article.

I *really* miss the pairing functionality, once I found it it a few years back it was obvious to me what it was and it became the top main selling point of firefox to me.

The main benefits for me was:

* End to end encryption of bookmarks and passwords,

* Dead easy to get my passwords and bokmarks to any new device.

* Toghether with the master password that made my passwords protected on all my devices. The tricky thing was to realize that I had to have exactly the same master password on all devices. That wasn’t very obvious.

One use case that I couldn’t get my head around was this:

* I have my android device with me, I arrive at a new desktop installation and want to pair it using my android device. With some versions of FF it was possible to do with some not. When it worked I found this immensely useful and easy to use!

Back to the current situation, as it is now, the passwords are indeed encrypted when in transit between devices but they can no longer be viewed as encrypted when at rest at each device.

Why can’t you just merge the sync account password and the master password such that FF optionally prompts for the sync password everytime I start the browser? That would turn the sync password into the key that encrypts the passwords at rest in each device and it would make a lot of sense IMHO.

I started to use the master password last year when a whole bunch of Google Chrome users discovered that their passwords were stored unencrypted in their browsers, quite easily accessible under some obfuscated menu item. To my delight, by using the same master password on all my devices and the pairing functionality I could achive both secure local storage and getting my passwords synced between devices in a dead simple way.

Therefore, I’m really suggesting you should increase the demand on high quality sync password such that it can be used as the master password key as well. That would recover the unique selling point FF had up until the most recent version.

Regards, Daniel Hegner

Could have just showed them the key and said to write it down or else.

[…] Last time I described the user difficulties we observed with the pairing-based Sync we shipped in Firefox 4.0. In late April, we released Firefox 29, with a new password-based Sync setup process. In this post, I want to describe the protocol we use in the new system, and their security properties. […]

Yeah, pairing really needs to come back.

Before, if someone wanted my passwords, they would need physical access to one of my computers with a Sync-enabled instance of Firefox. They would have to find a way to decrypt my hard drive and copy my Firefox credentials.

Now, they just have to guess my password.

But let’s say I want to do it right, and have my password be a randomly-generated, 256-bit ASCII string. Now, I have to manually type that in, or use an external password manager, or something like that. J-PAKE made that easy and secure.

Why am I being punished because idiot users didn’t understand how the original sync worked?