Google’s Protected Audience protects advertisers (and Google) more than it protects you

The announcement that Google would remove the ability to track people using cookies in its Chrome browser was met with some consternation from advertisers. After all, when your business relies so heavily on tracking, as is common in the advertising industry, removing the key means of performing that tracking is a bit of a big deal.

Google relies on tracking too, but this change has the potential to skew the advertising market in Google’s favor. For online advertisers looking to perform individualized ad targeting, tracking is a significant important source of visitor information. Smaller ad networks and websites depend on being able to source information about what people do on other sites in order to be competitive in the ruthless online advertising marketplace. Without that, these smaller players might be less able to connect visitors with the — often shady — trade in personal data.

On the other hand, entities like Google who operate large sites, might rely less on information from other sites. Losing the information that comes from tracking people might affect them far less when they can use information they gather from their many services.

So, while the privacy gains are clear — reducing tracking means a reduction in the collection and trade of information about what people do online — the competition situation is awkward. Here we have a company that dominates both the advertising and browser markets, proposing a change that comes with clear privacy benefits, but it will also further entrench its own dominance in the massively profitable online advertising market.

Protected Audience is a cornerstone of Google’s response to pressure from competition regulators, in particular the UK Competition and Markets Authority, with whom Google entered into a voluntary agreement in 2022. Protected Audience seeks to provide some counterbalance to the effects of better privacy in the advertising market.

We find Google’s claims about the effect of Protected Audience on advertising competition credible. The proposal could make targeted advertising better for sites that heavily relied on tracking in the past. That comes with a small caveat: complexity might cause a larger share of advertising profits to go to ad tech intermediaries.

However, the proposal fails to meet its own privacy goals. The technical privacy measures in Protected Audience fail to prevent sites from abusing the API to learn about what you did on other sites.

To say that the details are a bit complicated would be something of an understatement. Protected Audience is big and involved, with lots of moving parts, but it can be explained with a simple analogy.

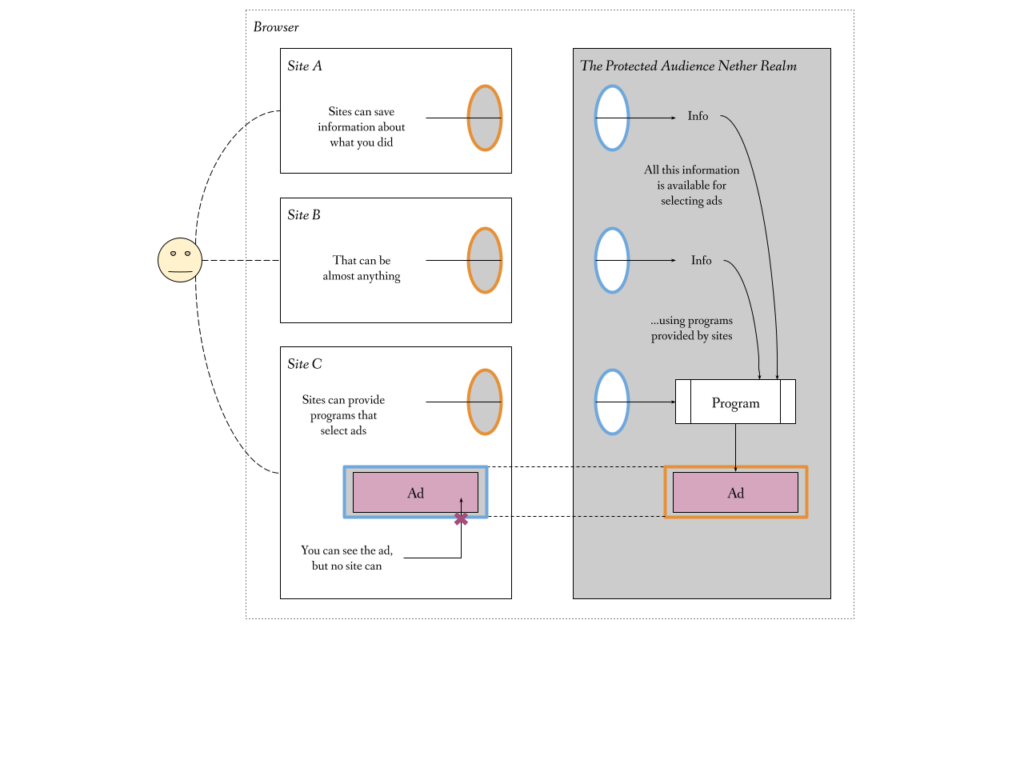

The idea behind Protected Audience is that it creates something like an alternative information dimension inside of your (Chrome) browser. In this alternative dimension, tracking what you saw and did online is possible. Any website can push information into that dimension. While we normally avoid mixing data from multiple sites, those rules are changed to allow that. Sites can then process that data in order to select advertisements. However, no one can see into this dimension, except you. Sites can only open a window for you to peek into that dimension, but only to see the ads they chose.

Leaving the details aside for the moment, the idea that personal data might be made available for specific uses like this, is quite appealing. A few years ago, something like Protected Audience might have been the stuff of science fiction. Protected Audience might be flawed, but it demonstrates real potential. If this is possible, that might give people more of a say in how their data is used. Rather than just have someone spy on your every action then use that information as they like, you might be able to specify what they can and cannot do. The technology could guarantee that your choice is respected.

Maybe advertising is not the first thing you would do with this newfound power, but maybe if the advertising industry is willing to fund investments in new technology that others could eventually use, that could be a good thing.

Sadly, Protected Audience fails in two ways. To be successful, it must process data without leaks. In a complex design like this, it is almost expected that there will be a few holes in the design. However, the biggest problem is that the browser needs to stop websites from seeing the information that they process.

Preventing advertising companies from looking at the information they process makes it extremely difficult to use Protected Audience. In response to concerns from these companies, Google loosened privacy protections in a number of places to make it easier to use. Of course, by weakening protections, the current proposal provides no privacy. In other words, to help make Protected Audience easier to use, they made the design even leakier.

A lot of these leaks are temporary. Google has a plan and even a timeline for closing most of the holes that were added to make Protected Audience easier to use for advertisers. The problem is that there is no credible fix for some of the information leaks embedded in Protected Audience’s architecture.

A stronger Protected Audience might lead us to ask some fairly challenging questions. We might ask whether objections to targeted advertising arise solely from the privacy problems with current technology? Or, is it the case that targeted manipulation itself is the problem? Targeted advertising is more effective because it uses greater information about its audience — you — to better influence your decisions. So would a system that prevented information collection, but still allowed advertisers to exercise that influence, be acceptable?

We would also need to decide to what extent a browser — a user agent — can justifiably act in ways that are not directly in the interests of its user. Protected Audience exists for the benefit of the advertising industry. A system that makes it easier to make websites supported by advertising has benefits. After all, advertising does have the potential to make content more widely accessible to people of different means, with richer people effectively subsidizing content for those of lesser means. A stronger Protected Audience might then provide people with a real, if indirect, benefit. Does that benefit outweigh the costs of giving advertisers greater influence over our decision-making?

With Protected Audience as it is today, we can simply set those questions aside. In failing to achieve its own privacy goals, Protected Audience is not now — and maybe not ever — a good addition to the Web.

Read our much longer analysis of Protected Audience for more details.