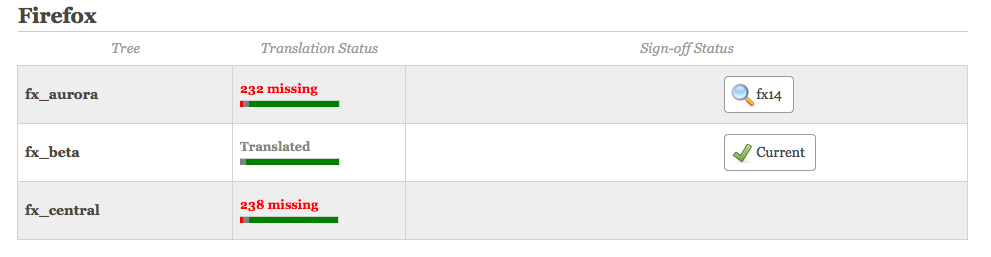

Wait, what, migrating to the rapid release process? Aren’t we, like, doing that? Well, not in the data models that drive the l10n dashboard. What follows is two-fold, for one, why would I be hacking on a patch for half a year? But also, there are some interesting technical tidbits on how to do intensive data migrations in a django project. I’ll link to the actual code in full later, right now the patch is still in flux. I’ll need to write this stuff down to get a review on the patch, so why not here.

I’ve blogged about data models before, but here’s a quick glossary:

Tree models a set of repositories to run automated tests against, namely, compare-locales. AppVersion models the thing we’re shipping, say Firefox 3.6 or Firefox 13.

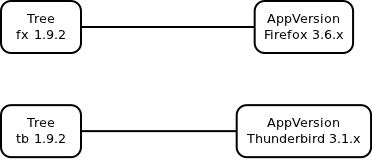

When gandalf and I originally designed this part of the dashboard, the relationship between what we build and what we shipped was static, kinda like

Small caveat, for AppVersions we’re not building right now, the old tree is stored as lasttree. We’ll need that data further down.

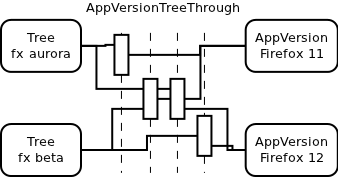

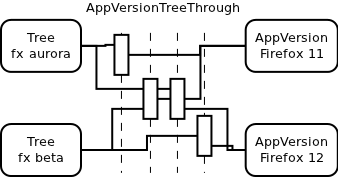

The rapid release process now lets AppVersions jump from Tree to Tree like little birds. So we need to have some intermediary that models that relationship, with start and end time. More like

Sorry for the ugliness, but that’s the pretty part so far.

Let’s start with doing that migration. Be warned, it’s migration 1 out of 4.

This first migration covers the sql schema, and persists the existing links between AppVersions and Trees. We’ll want to drop two ForeignKey columns for tree and lasttree from AppVersion, and add a ManyToMany table for the new relationship. Plus constraints and indices, sure. As I don’t speak sql, I want to use the ORM as much as I can, which sounds like one couldn’t. Enter a fake migration app that mimics the import pieces of our shipping app. It’ll contain a subset of AppVersion to the extent we need it, and the intermediate model, AppVersionTreeThrough. This needs to be really fake code, as you shouldn’t rely too much on the version of the code on disk to be really what you need for this db migration step. I cheat a bit on that, though. The import trick here is that the fake AppVersion contains both the old and the new fields, and that the fake AppVersionTreeThrough matches the one you migrate to in all flags and fields.

Now, getting django to eat a fake app is tricky. You need a module for the app, and that module needs to have a models module. Both need to be in sys.modules, and they need to have the __file__ properties set. Just because django is paranoid about equality of code and thinks it needs to verify location on disk. But hey, I can spoof all of that. Python ftw. Then you create a meta class, copying most data for db and management from your original app, and with that meta, create Model subclasses.

Ok, so now we have python code to do the migration, but we don’t have the SQL tables and columns yet. Let’s get our fingers dirty with that.

from django.core.management import color, sql

style = color.no_style()

sql.sql_all(mig_module.models, style, ship_connection)

This is going to return a list of all CREATE TABLE, CREATE INDEX, ALTER TABLE ADD CONSTRAINT sql commands for our fake migration models. The migration code inspects that, and creates the many-to-many table, adds constraints and indices, and tweaks the CREATE TABLE statement for AppVersion to just pull out the SQL definitions for the columns. Those get inserted into ALTER TABLE ADD COLUMN statements, and then we execute all that.

At this point, the database contains the old columns with the old data, and the new empty tables (and columns).

Now migrate the data, with the help of the our intermediate classes that can create the django orm magic. As we’re still in the first phase of our migration, let’s not overrotate and just make links between AppVersion and Tree over all time for those that are currently bound, and for those that used to be linked (read lasttree), make the end time just now(). We’ll fix that later. That’s a nice and easy loop.

Now we’ve used our migration app to the extent we need. It’d be nice if we could just leave it with that, but we’ve got to tear it down, because otherwise the validation step will complain about multiple apps referring to the same tables. Module caches in django are tough, the following code does that at least for 1.3:

# prune "migration_phase_1" app again

del settings.INSTALLED_APPS[-1]

from django.db.models import loading

loading.cache.app_models.pop('migration_phase_1', None)

loading.cache.register_models('migration_phase_1') # clear cache

# empty sys modules from our fake modules

sys.modules.pop(mig_name)

sys.modules.pop(mig_models_name)

And, yes, now we can DROP stuff, at least when using mysql. sqlite doesn’t do that, and in contrast to peterbe, I don’t mind postgres ;-). Of course, as django adds constraints with rather arbitrary names, the best thing we can do is inspect the database for the actual names of those, and then we drop’em, and the columns.

And if you think this blog post is too long, you’re right. Let’s talk about the migrations 2-4.

The second migration just inspects our actual builds, and adjusts the start and end times for stuff that’s not on the rapid release cycle, and old.

The third migration fights the past. To make our mismatching data model work for the rapid cycle, I replicated a lot of history data each time we migrated appversions, to a newly created set of appversions for that cycle. Now that our data model gets that right, this migration searches for that data (Signoff entries, and their associated Action ones), and deletes them.

The forth migration sets the start and end times for the rapid release cycle, including the off-times for Firefox 5, and moves the Signoff entries from the long running aurora AppVersion to the respective AppVersions on aurora at the time. Not too bad, but really loads of weird data, and it gets worse every six weeks :-).

Phew. You made it. Now all I need to do is to fix the code that uses all that data.