The Attention War. There have been many headlines related to it in the past decade. This is the idea that apps and companies are stealing attention. It’s the idea that technologists throw up ads on websites in a feeble attempt to get the attention of the people who visit the website.

In tech, or any industry really, people often say something to the effect of, “well if the person using this product or service only read the instructions, or clicked on the message, or read our email, they’d understand and wouldn’t have any problems”. We need people’s attention to provide a product experience or service. We’re all in the “attention war”, product designers and users alike.

And what’s a sure-fire way to grab someone’s attention? Interruptions. Regardless if they’re good, bad, or neutral. Interruptions are not necessarily a “bad” thing, they can also lead to good behavior, actions, or knowledge.

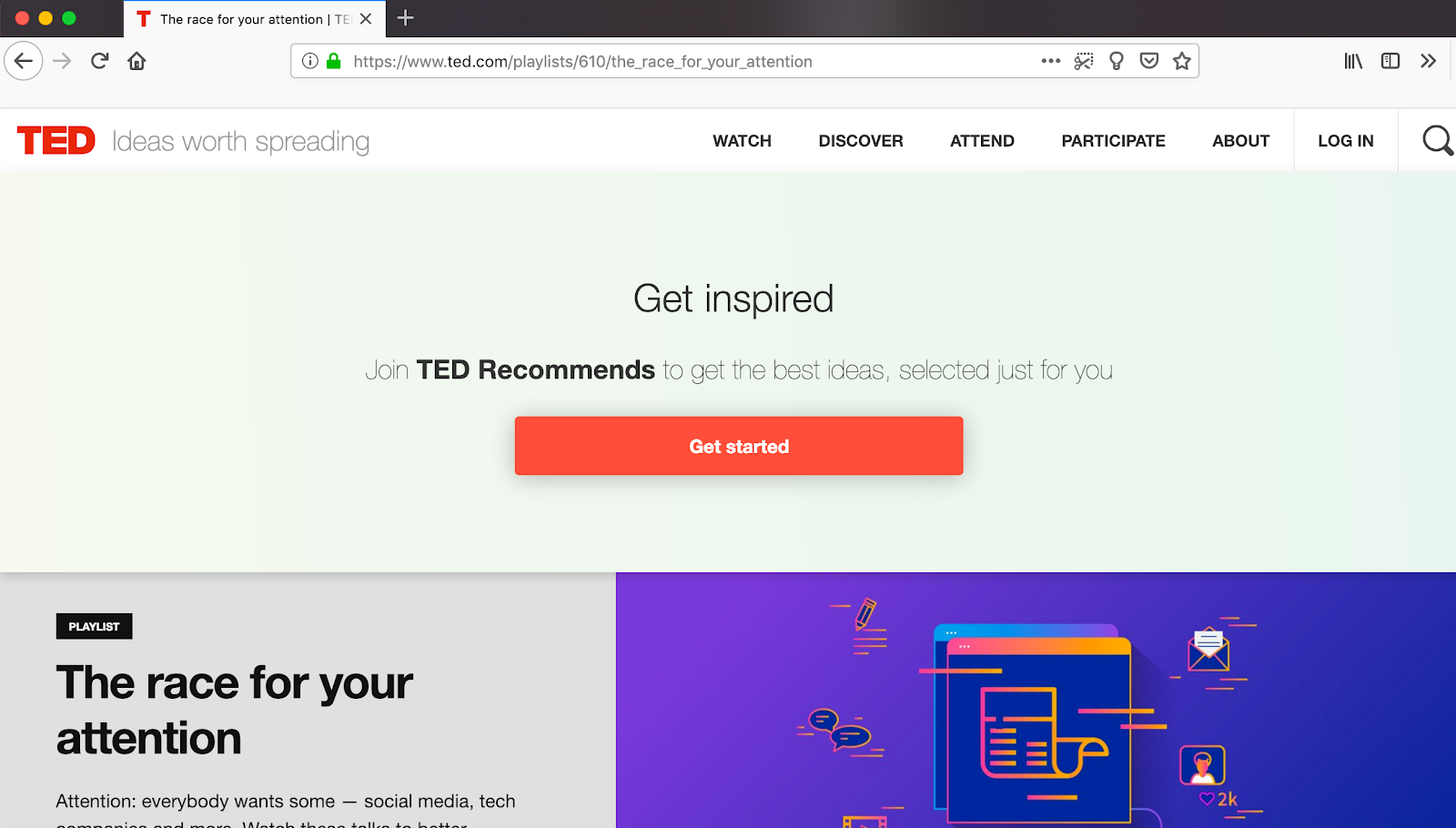

Even on a webpage that has a playlist of talks about “The race for your attention”, there’s a giant banner in attempt to get your attention to sign up for a recommendation service.

Here are a couple questions the Firefox Team had about interruptions:

- “How do participants feel about interruptions?”

- “Can participants distinguish between the sources of interruptions? (i.e. Can they tell if the interruption is from Firefox, a website, or the operating system?)”

To answer the questions, I ran a user research study about the interruptions people receive while using Firefox. Eight participants were in a week-long study. Each participant used Firefox as their main browser on their laptop. Four participants agreed to record their browsing sessions over the course of the week, and six participants agreed to share their browsing analytics with us. I logged interruptions that came from the operating system, desktop software, Firefox, and websites. All participants were interviewed on the first day and last day. On the last day, I asked each participant to complete five tasks that would trigger interruptions to gauge understanding, behavior, and attitudes towards interruptions.

Before I answer the two questions from above, I’ll describe how I categorized interruptions.

Stopping Power

To analyze the data, I coded each interruption in terms of its stopping power. Mehrotra et al. coded interruptions as “low priority” and “high priority” depending on if the interruption stopped a person from completing their task [1]. Similarly, I coded each interruption as “low stopping power”, “medium stopping power”, and “high stopping power” (examples in the figures below). I defined stopping power as how much the design & implementation of an interruption makes it so that the user must interact with it to continue using the system. From the recorded interviews and browsing sessions (excluding the five tasks that triggered interruptions), I logged 83 low stopping power interruptions, 37 medium, and 15 high.

An example of a “low stopping power” interruption: Screenshot that shows badged icons on the browser toolbar.

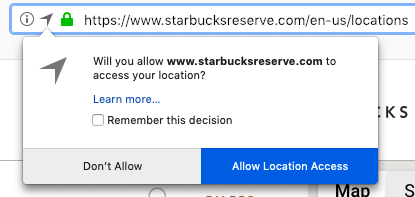

An example of a “medium stopping power” interruption: Screenshot from a participant’s screen. Location permission doorhanger.

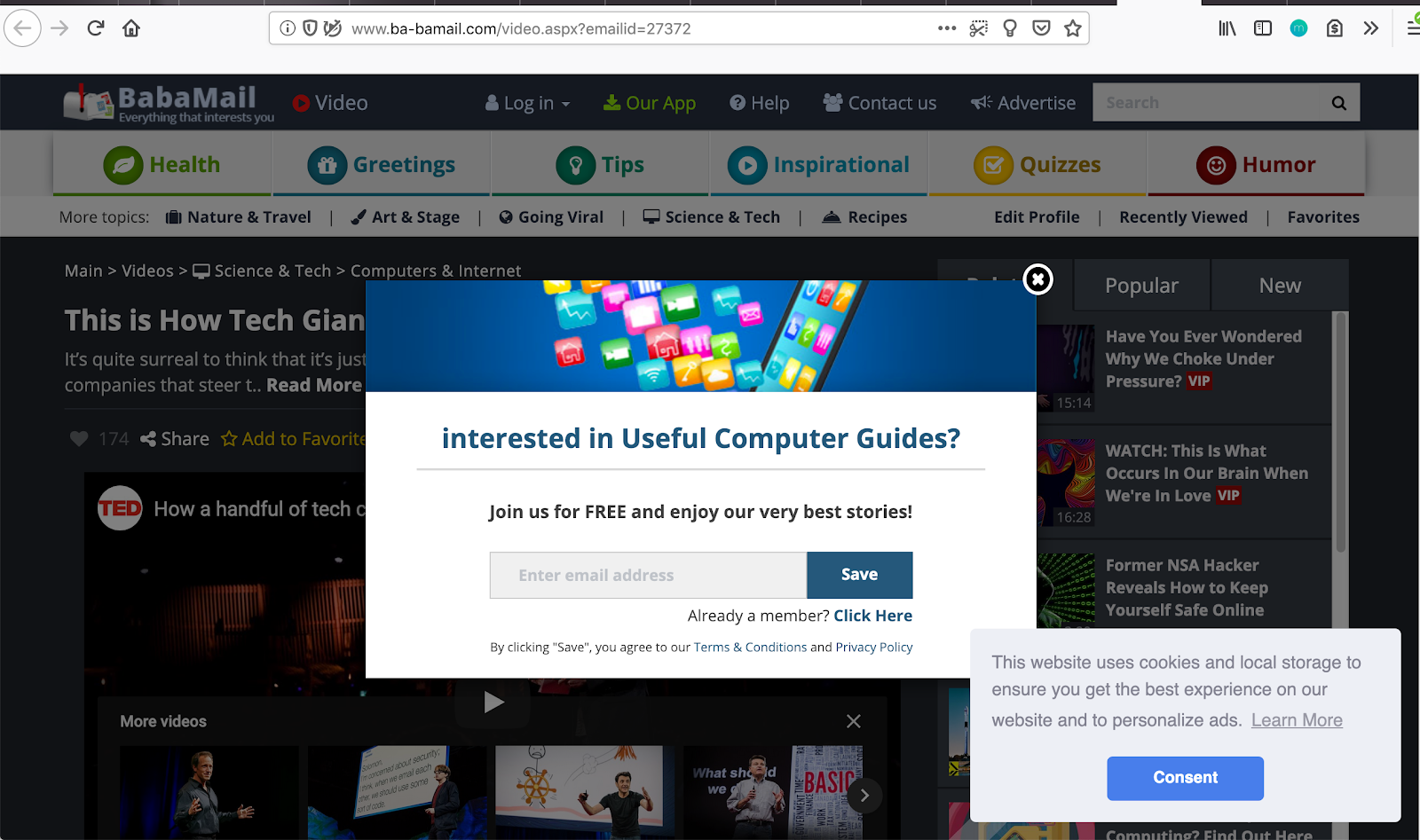

An example of a “high stopping power” interruption: Screenshot of a website modal asking for you to sign up.

Now I’ll move on to answer our two research questions.

1. How did participants feel about interruptions?

Participants care about their safety and saving time

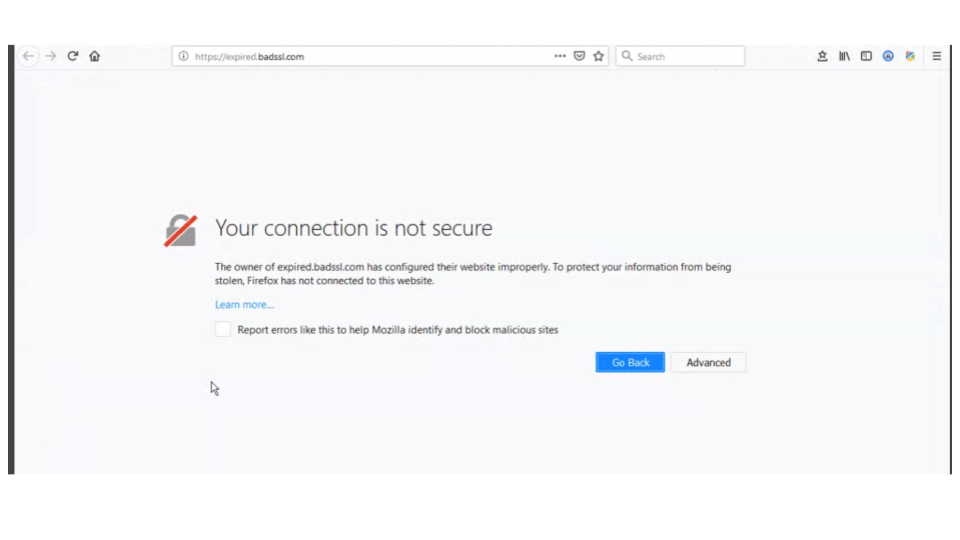

When I asked participants how they felt about the 5 interruptions they experienced during the post interview, a clear theme was safety. One task was for participants to visit a “Bad SSL*” page. This happens when a website has a malformed or outdated security certificate. An error will appear and you’ll see a message like the screenshot below: “Your connection is not secure”.

Screenshot of an error page that appears when the website’s security certificate is out of date.

A couple participants were frustrated at first with the idea of encountering this page, because they would not be able to get to the website they wanted to get to, but then participants expressed an appreciation for it saying, like one participant: “now that I’ve read it, I suppose it’s trying to help” and another saying “I like that it’s protecting me”.

*SSL stands for Secure Sockets Layer and is a security protocol where websites share a certificate to verify their identity. Without a certificate to verify their identity, Firefox can’t be sure that the website is who it says it is.

Some participants were annoyed by interruptions, others could care less.

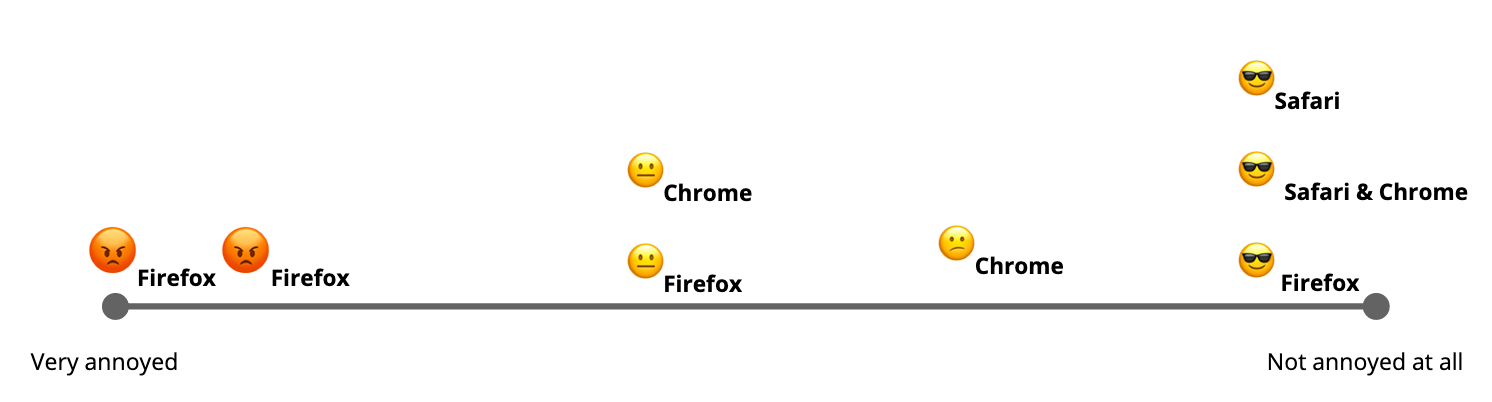

A visual scale of: “How annoyed were participants about interruptions they received while using Firefox?” Each emoji is one participant. The subscript is the browser they use the most outside of the research study. I did not ask participants to measure their own annoyance, but rather came up with this scale during analysis of interview responses.

Participants reacted to interruptions differently, as shown by the scale above. This study was not able to determine the factors that impacted their level of annoyance — we would need to gather more data to determine that. However, it’s important to note that not everyone will react the same to interruptions. Some will make comments like one of the participants that it “feels like a gun shooting range” (where interruptions appear all over the place), and others will barely notice interruptions at all.

2. “Can participants distinguish between the sources interruptions? Can they tell if the interruption is from Firefox, a website, or the operating system?”

Most participants could not tell you the source of the interruption.

Only two of the eight participants could differentiate between all sources. They confidently knew if an interruption was from the operating system, website, or browser.

Four of the eight participants could differentiate between an operating system and a browser/website notification but NOT between a browser and a website notification. For example, a participant could tell that operating system was asking to perform an update. However, a participant could not tell if the website or browser was asking to save their credit card information.

One of the eight participants could not tell the difference between any of them. They thought that a notification from desktop email software was coming from Firefox, and wondered why other browsers did not do that.

Why is this important?

Do people really need to know the source of an interruption, if it does not hinder them from completing their task? Yes. An understanding of the source of the interruption is important for safety (i.e. people know where their data is and who it’s being shared with), and for mitigating potential annoyance with Firefox for things that Firefox is not responsible for.

Are you a designer or product manager?

Every time your product or service is considering interrupting someone, ask:

- Is it worth stopping someone for?

- Are you helping the person using your product or service to be more safe, or save time?

As I saw from the hours of browser recordings, we live in a vast sea of interruptions. Let’s be careful how we add to the ever-growing pile.

Acknowledgements (alphabetical by first name)

Thank you to my colleagues at Mozilla for helping with this study! Thanks to Aaron Benson, Alice Rhee, Amy Lee, Amy Tsay, Betsy Mikel, Brian Jones, Bryan Bell, Chris More, Chuck Harmston, Cindy Hsiang, Emanuela Damiani, Frank Bertsch, Gemma Petrie, Grace Xu, Heather McGaw, Javaun Moradi, Kamyar Ardekani, Kev Needham, Maria Popova, Meridel Walkington, Michelle Heubusch, Peter Dolanjski, Philip Walmsley, Romain Testard, Sharon Bautista, Stephen Horlander, Tim Spurway

Reference

[1] Mehrotra, A., Pejovic, V., Vermeulen, J., Hendley, R., & Musolesi, M. (2016). My Phone and Me (pp. 1021–1032). Presented at the the 2016 CHI Conference, New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. http://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858566.

Originally published on medium.com.