Here, Michael Johnson (MJ), founder of johnson banks, and Tim Murray (TM), Mozilla creative director, have a long-distance conversation about the Mozilla open design process while looking in the rear-view mirror.

TM: We’ve come a long way from our meet-in-the-middle in Boston last August, when my colleague Mary Ellen Muckerman and I first saw a dozen or so brand identity design concepts that had emerged from the studio at johnson banks.

MJ: If I recall, we didn’t have the wall space to put them all up, just one big table – but by the end of the day, we’d gathered around seven broad approaches that had promise. I went back to London and we gave them a good scrubbing to put on public show.

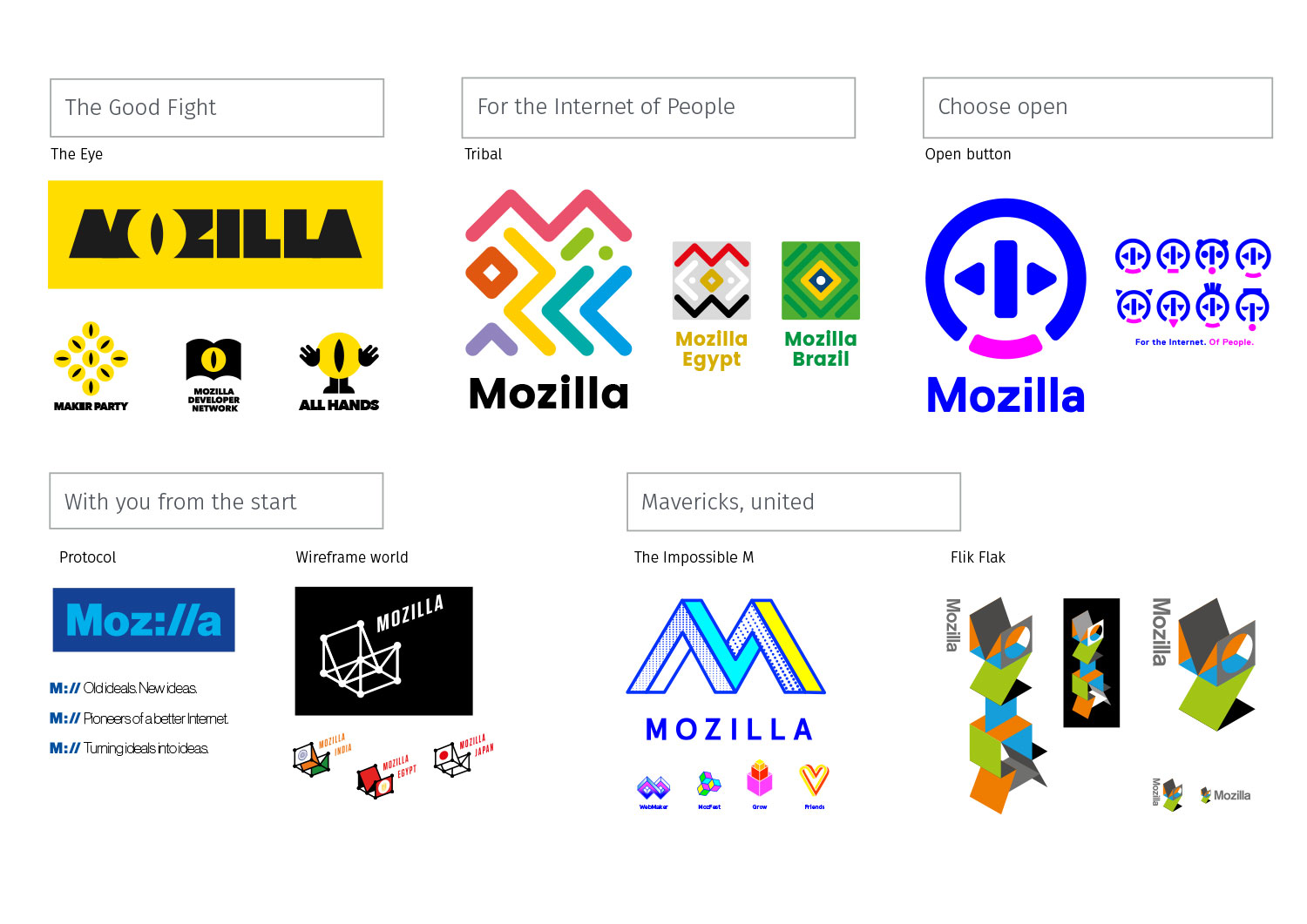

It’s easy to see, in retrospect, certain clear design themes starting to emerge from these earliest concepts. Firstly, the idea of directly picking up on Mozilla’s name in ‘The Eye’ (and in a less overt way in the ‘Flik Flak’). ‘The Eye’ also hinted at the dinosaur-slash-Godzilla iconography that had represented Mozilla at one time. We also see at this stage the earliest, and most minimal version of the ‘Protocol’ idea.

TM: You explored several routes related to code, and ‘Protocol’ was the cleverest. Mary Ellen and I were both drawn to ‘The Eye’ for its suggestion that Mozilla would be opinionated and bold. It had a brutal power, but we were also a bit worried that it was too reminiscent of the Eye of Sauron or Monsters, Inc.

MJ: Logos can be a bit of a Rorschach test, can’t they? Within a few weeks, we’d come to a mutual conclusion as to which of these ideas needed to be left on the wayside, for various reasons. The ‘Open button’, whilst enjoyed by many, seemed to restrict Mozilla too closely to just one area of work. Early presentation favourites such as ‘The Impossible M’ turned out to be just a little too close to other things out in the ether, as did Flik Flak – the value, in a way, of sharing ideas publicly and doing an impromptu IP check with the world. ‘Wireframe World’ was to come back, in a different form in the second round.

TM: This phase was when our brand advisory group, a regular gathering of Mozillians representing different parts of our organization, really came into play. We had developed a list of criteria by which to review the designs – Global Reach, Technical Beauty, Breakthrough Design, Scalability, and Longevity – and the group ranked each of the options. It’s funny to look back on this now, but ‘Protocol’ in its original form received some of the lowest scores.

MJ: One of my sharpest memories of this round of designs, once they became public was how many online commentators critiqued the work for being ‘too trendy’ or said ‘this would work for a gallery not Mozilla’. This was clearly going to be an issue because, rightly or wrongly, it seemed to me that the tech and coding community had set the bar lower than we had expected in terms of design.

TM: A bit harsh there, Michael? It was the tech and coding community that had the most affinity for ‘Protocol’ in the beginning. If it wasn’t for them, we might have let it go early on.

MJ: Ok, that’s a fair point. Well, we also started to glimpse what was to become another recurring theme – despite johnson banks having been at the vanguard of broadening out brands into complete and wide-ranging identity systems, we were going to have to get used to a TL:DR way of seeing/reading that simply judged a route by its logo alone.

TM: Right! And no matter how many times we said that these were early explorations we received feedback that they were too “unpolished.” Meanwhile, others felt that they were too polished, suggesting that this was the final design. We were whipsawed by feedback.

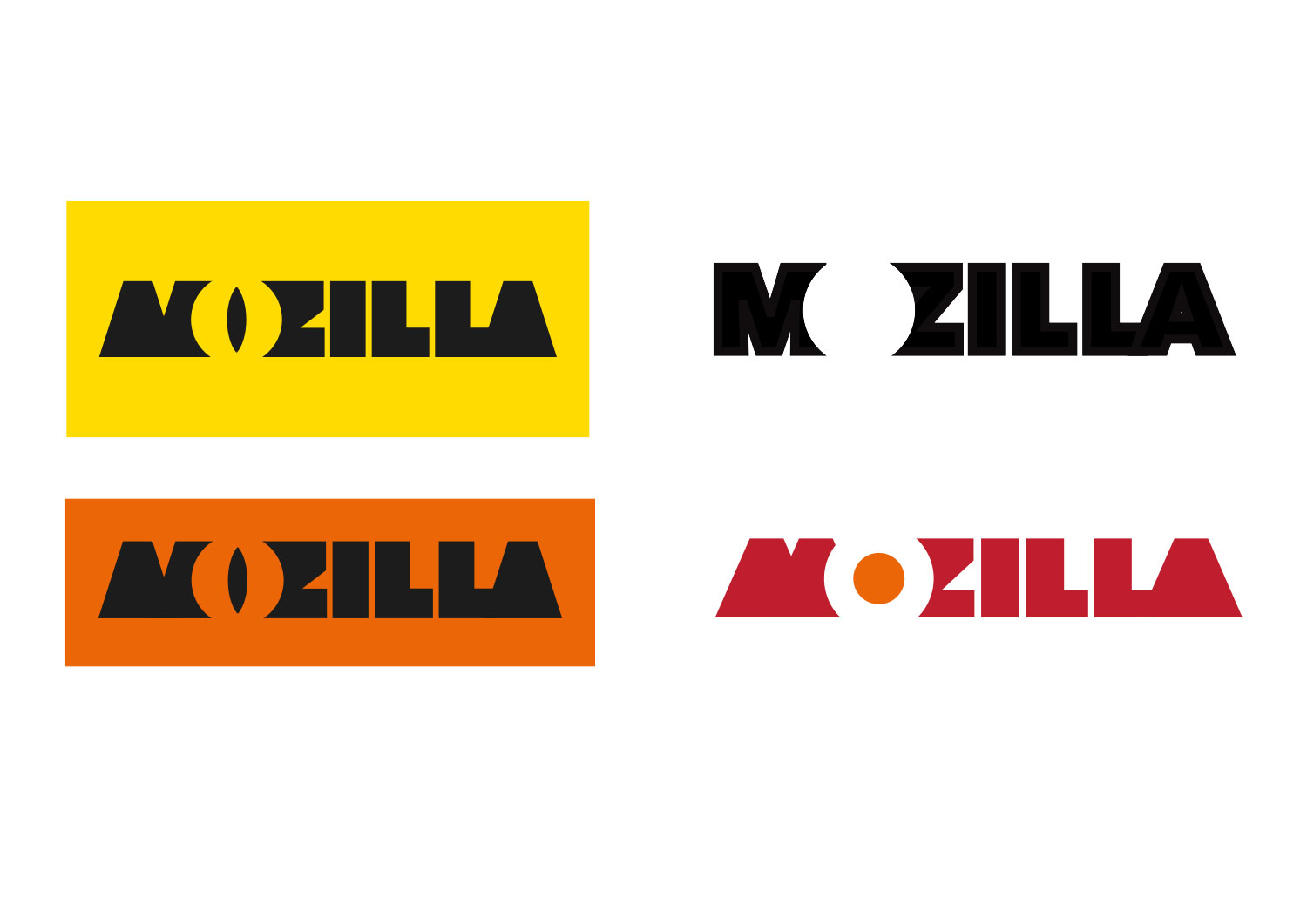

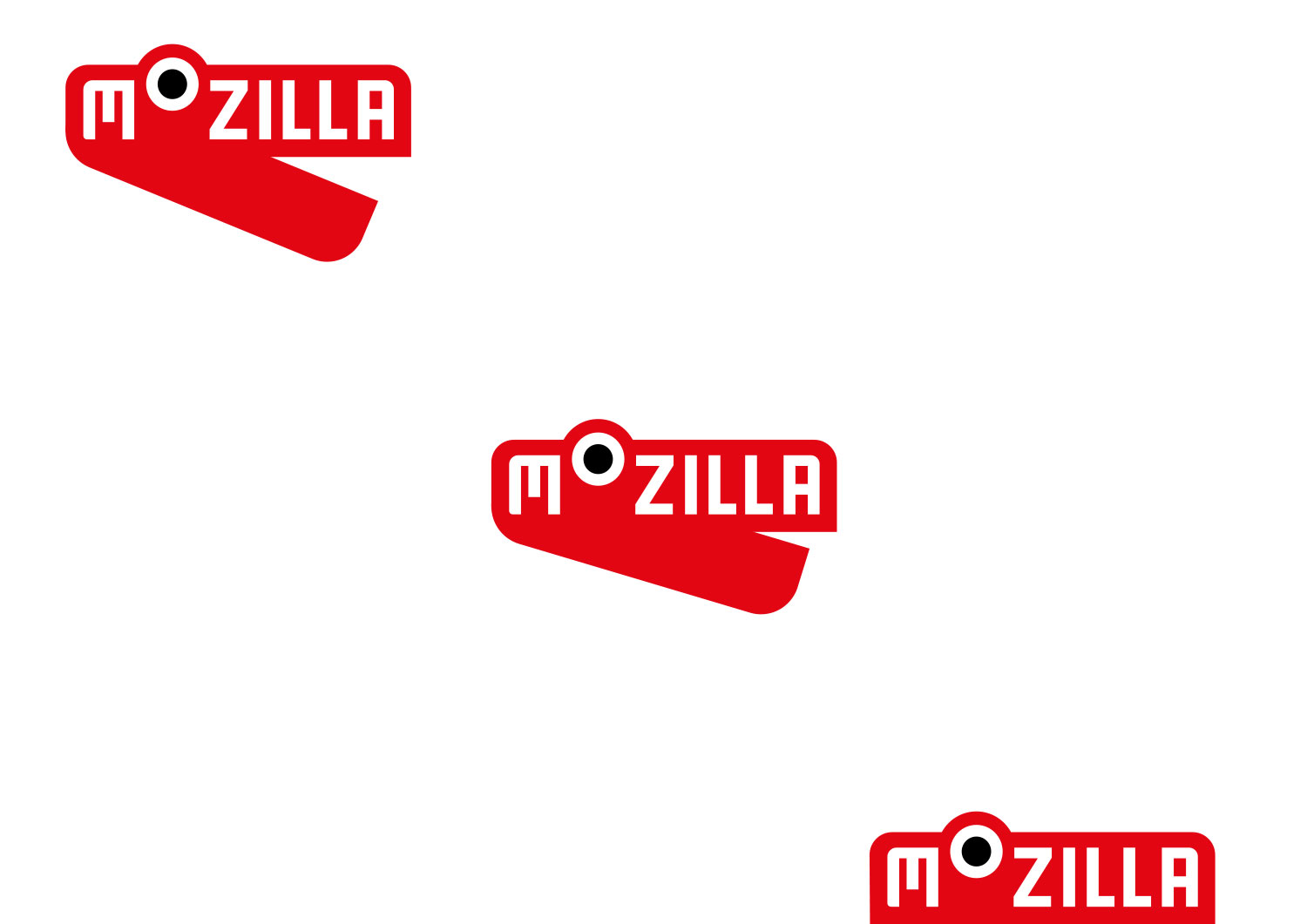

MJ: Whilst to some the second round seemed like a huge jump from the first, to us it was a logical development. All our attempts to develop The Eye had floundered, in truth – but as we did that work, a new way to hint at the name and its heritage had appeared. It was initially nicknamed ‘Chomper’, but was then swiftly renamed ‘Dino 2.0’. We see, of course the second iteration of Protocol, this time with slab-serifs. And two new approaches – Flame and Burst.

TM: I kind of fell in love with ‘Burst’ and ‘Dino 2.0’ in this round. I loved the idea behind ‘Flame’ — that it represented both our eternal quest to keep the Internet alive and healthy and the warmth of community that’s so important to Mozilla — but not this particular execution. To be fair, we’d asked you to crank it out in a matter of days.

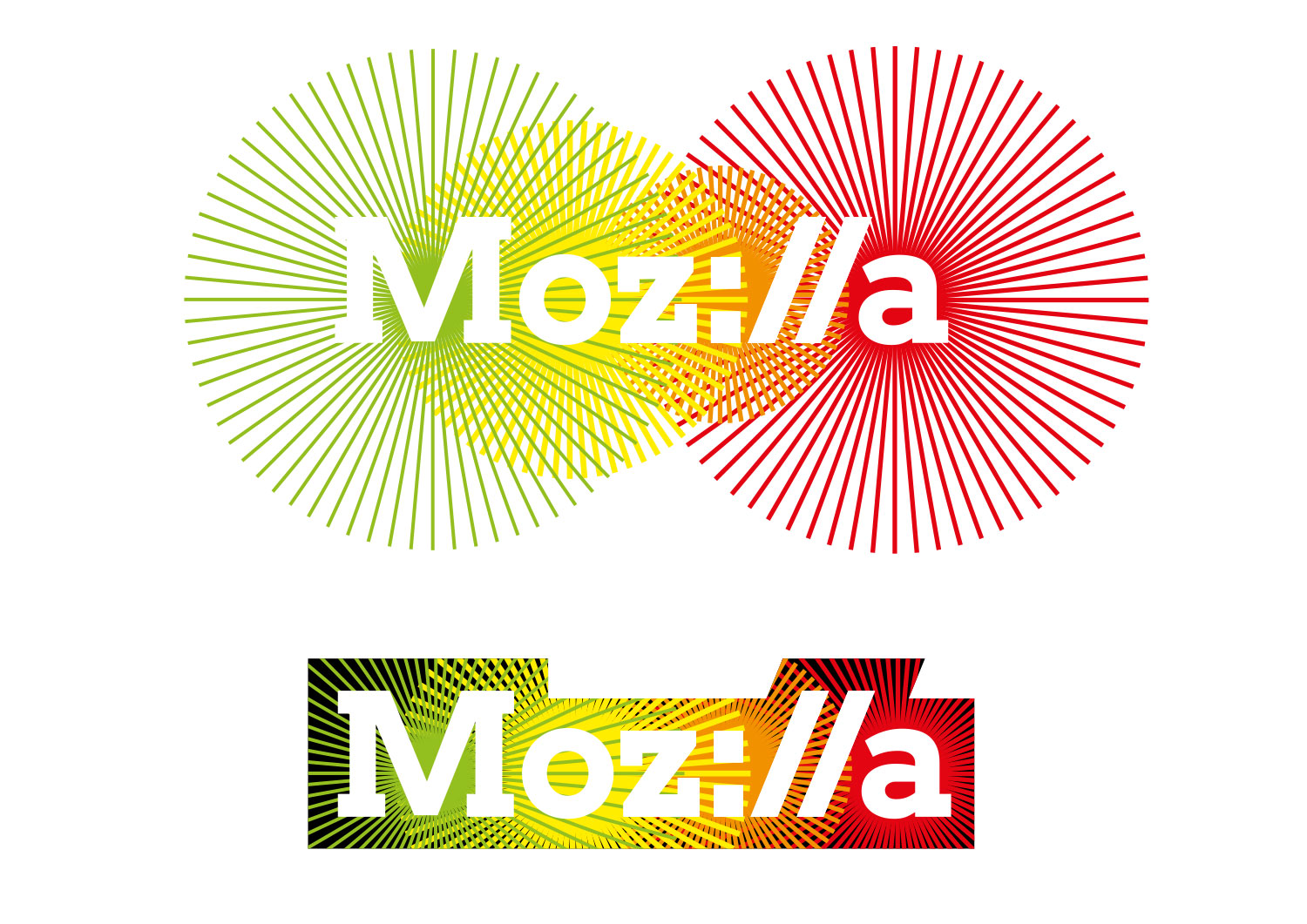

MJ: Well, yes that’s true. With ‘Flame’ we then suffered from too close a comparison to all the other flame logos out in there in the ether, including Tinder. Whoops! ‘Burst’ was, and still is, a very intriguing thought – that we see Mozilla’s work through 5 key nodes and questions, and see the ‘M’ shape that appears as the link between statistical points.

TM: Web developers really rebelled against the moire of Burst, didn’t they? We now had four really distinct directions that we could put into testing and see how people outside of Mozilla (and North America) might feel. The testing targeted both existing and desired audiences, the latter being ‘Conscious Choosers’, a group of people who made decisions based on their personal values.

MJ: We also put these four in front of a design audience in Nashville at the Brand New conference, and of course commentary lit up the Open Design blog. The results in person and on the blogs were pretty conclusive – that Protocol and Dino 2.0 were the clear favourites. But one set of results were a curve ball – that the overall ‘feel’ of Burst was enjoyed by a key group of desired (and not current) supporters.

TM: This was a tricky time. ‘Dino’ had many supporters, but just about as many vocal critics. As soon as one person remarked “It looks like a stapler,” the entire audience of blog readers piled on, or so it seemed. At our request, you put the icon through a series of operations that resulted in the loss of his lower jaw. Ouch. Even then, we had to ask, as beloved as this dino character was for its historical reference to the old Mozilla, would it mean anything to newcomers?

MJ: Yes, this was an odd period. For many, it seemed that the joyful and playful side of the idea was just too much ‘fun’ and didn’t chime with the desired gravitas of a famous Internet not-for-profit wanting to amplify its voice, be heard and be taken seriously. Looking back, Dino died a slow and painful death.

TM: Months later, rogue stickers are still turning up of the ‘Dino’ favicon showing just the open jaws without the Mozilla word mark. A sticker seemed to be the perfect vehicle for this design idea. And meanwhile, ‘Protocol’ kept chugging along like a tortoise at the back of the race, always there, never dropping out.

MJ: We entered the autumn period in a slightly odd place. Dino had been effectively trolled out of the game. Burst had, against the odds, researched well, but more for the way it looked than what it was trying to say. And Protocol, the idea that had sat in the background whilst all around it hogged the spotlight, was still there, waiting for its moment. It had always researched well, especially with the coding community, and was a nice reminder of Mozilla’s pioneering spirit with its nod to the http protocol.

TM: To me though, the ‘Protocol’ logo was a bit of a one-trick pony, an inside joke for the coding community that didn’t have as much to offer to the non-tech world. You and I came to the same conclusion at the same time, Michael. We needed to push ‘Protocol’ further, maybe even bring over some of the joy and color of routes such as ‘Burst’ and the fun that ‘Dino’ represented.

MJ: Our early reboot work wasn’t encouraging. Simply putting the two routes together, such as this, looked exactly like what it is: two routes mashed together. A boardroom compromise to please no-one. But, gradually, some interesting work started to emerge, from different parts of the studio.

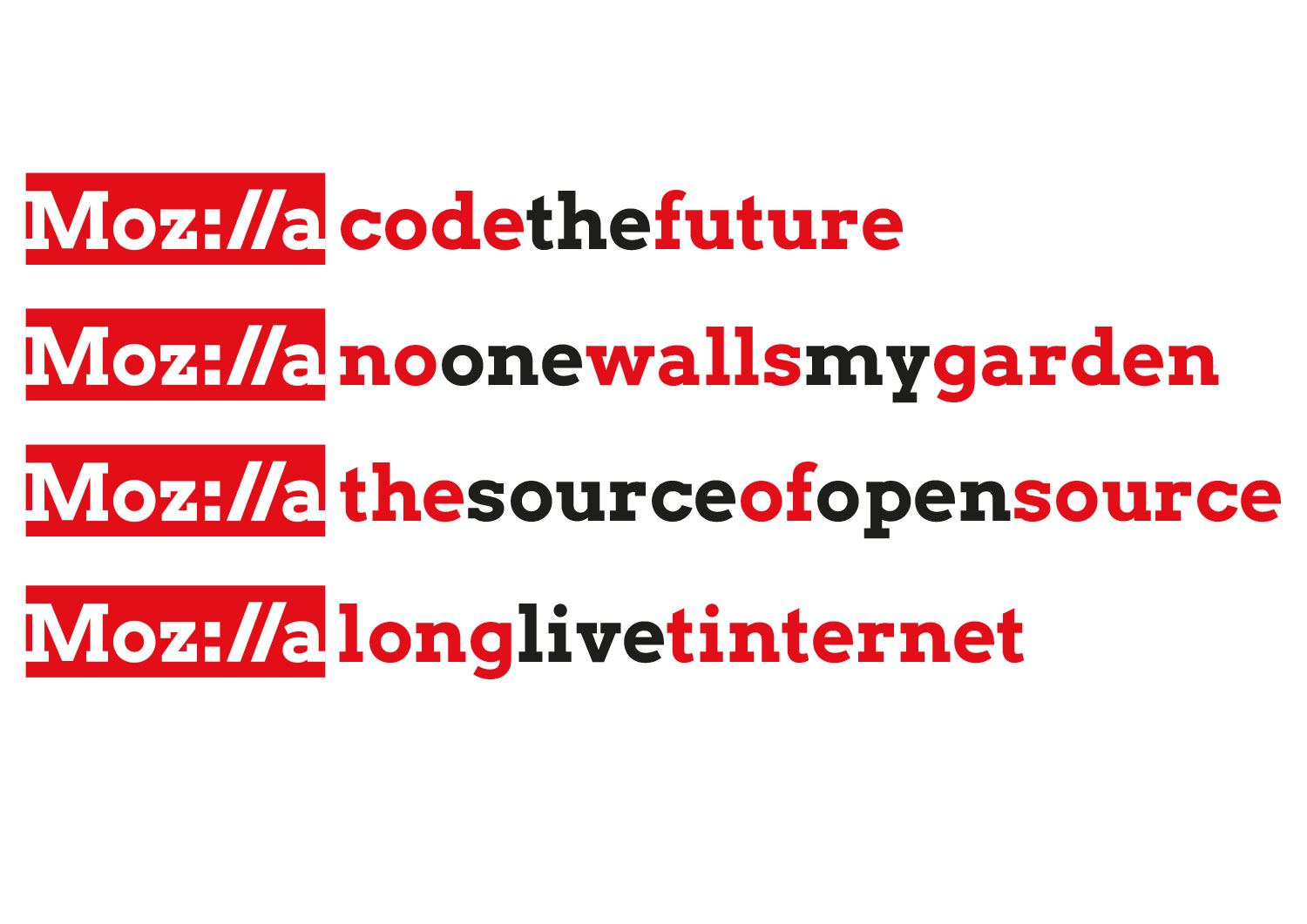

We began to think more about how Mozilla’s key messages could really flow from the Moz://a ‘start’, and started to explore how to use intentionally attention grabbing copy-lines next to the mark, without word spaces, as though written into a URL.

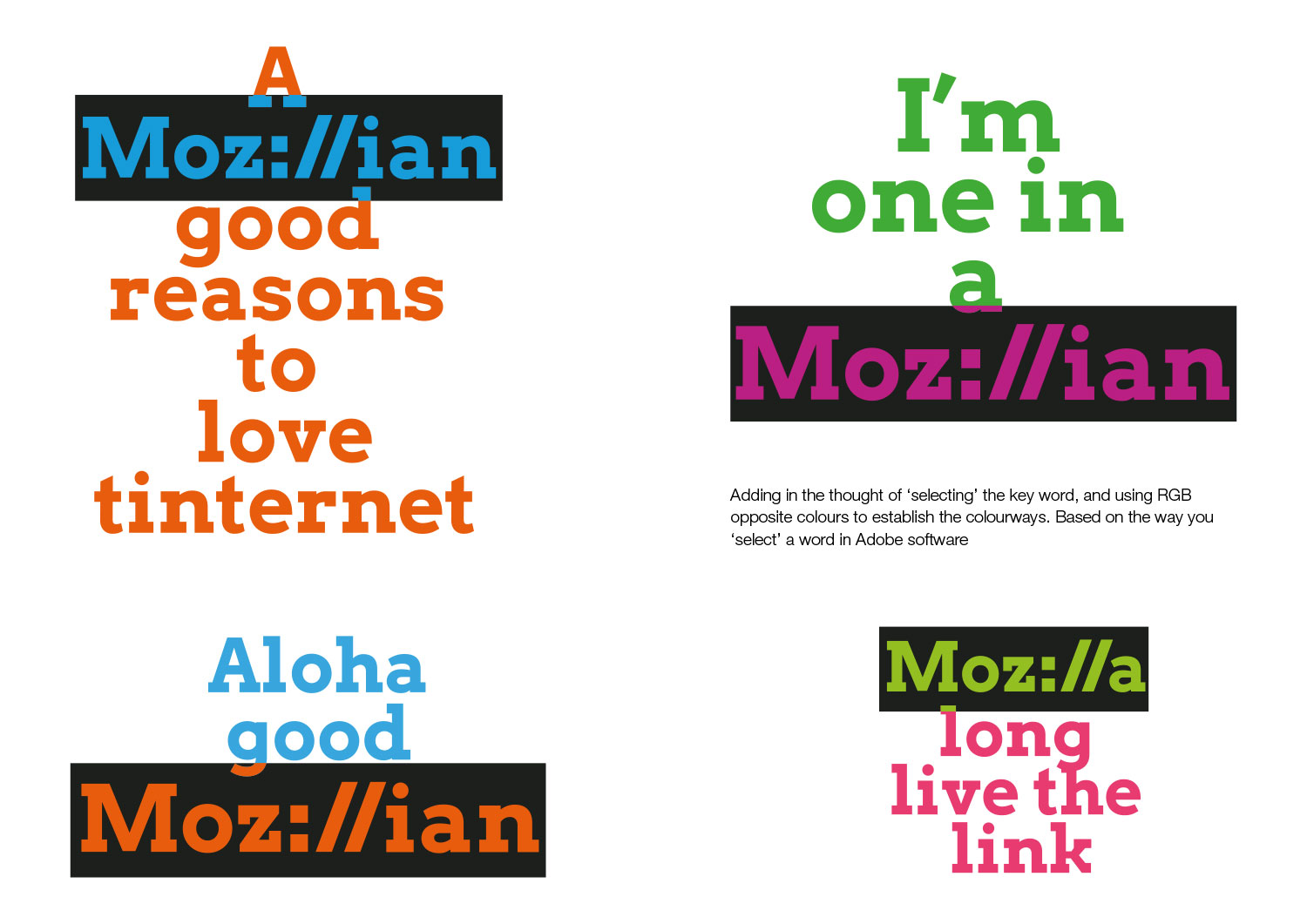

We also experimented with the Mozilla wordmark used more like a ‘selected’ item in a design or editing programme – where that which is selected reverses out from that around it.

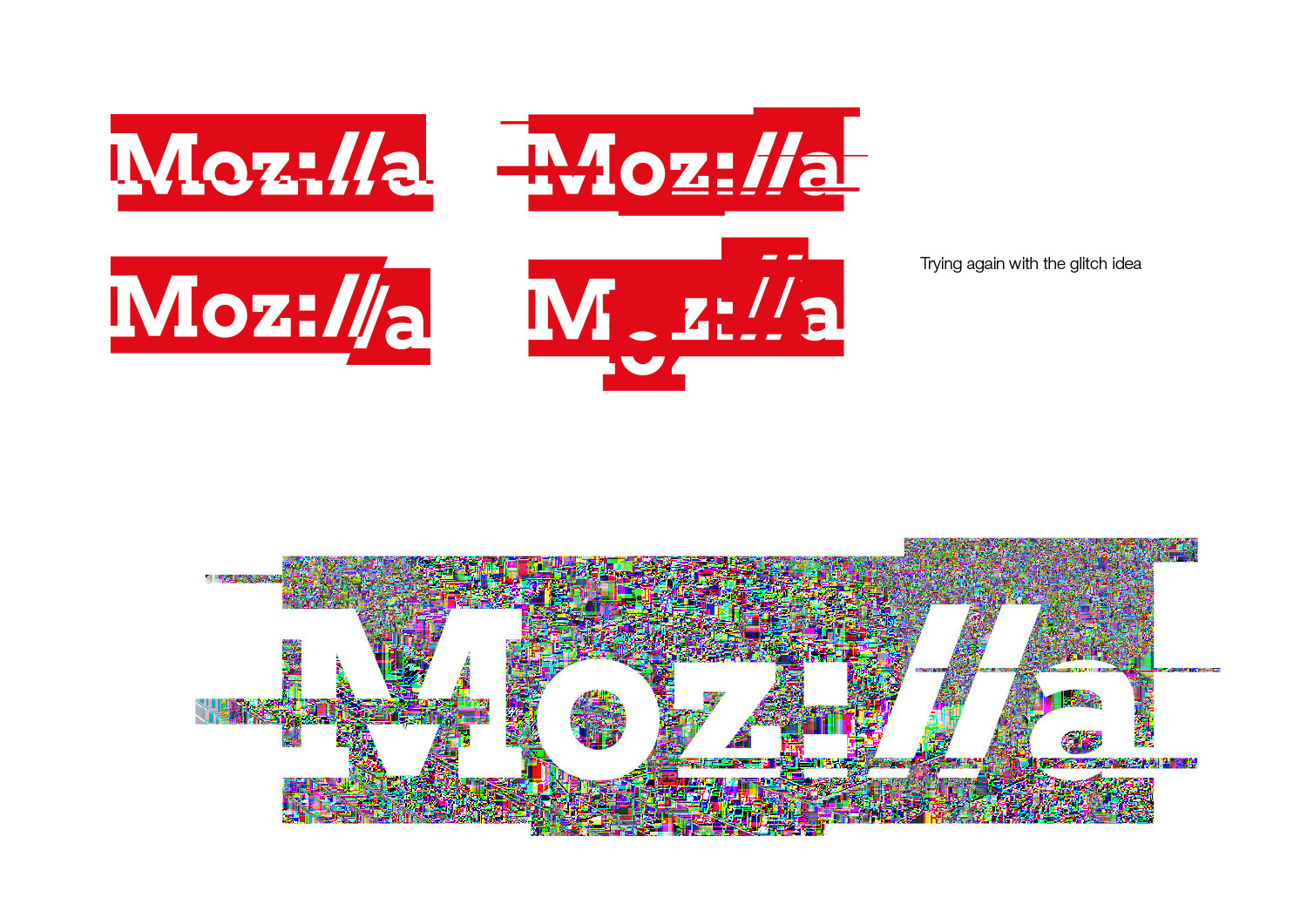

From an image-led perspective, we also began to push the Mozilla mark much further, exploring if it could be shattered, deconstructed or glitched, in so becoming a much more expressive idea.

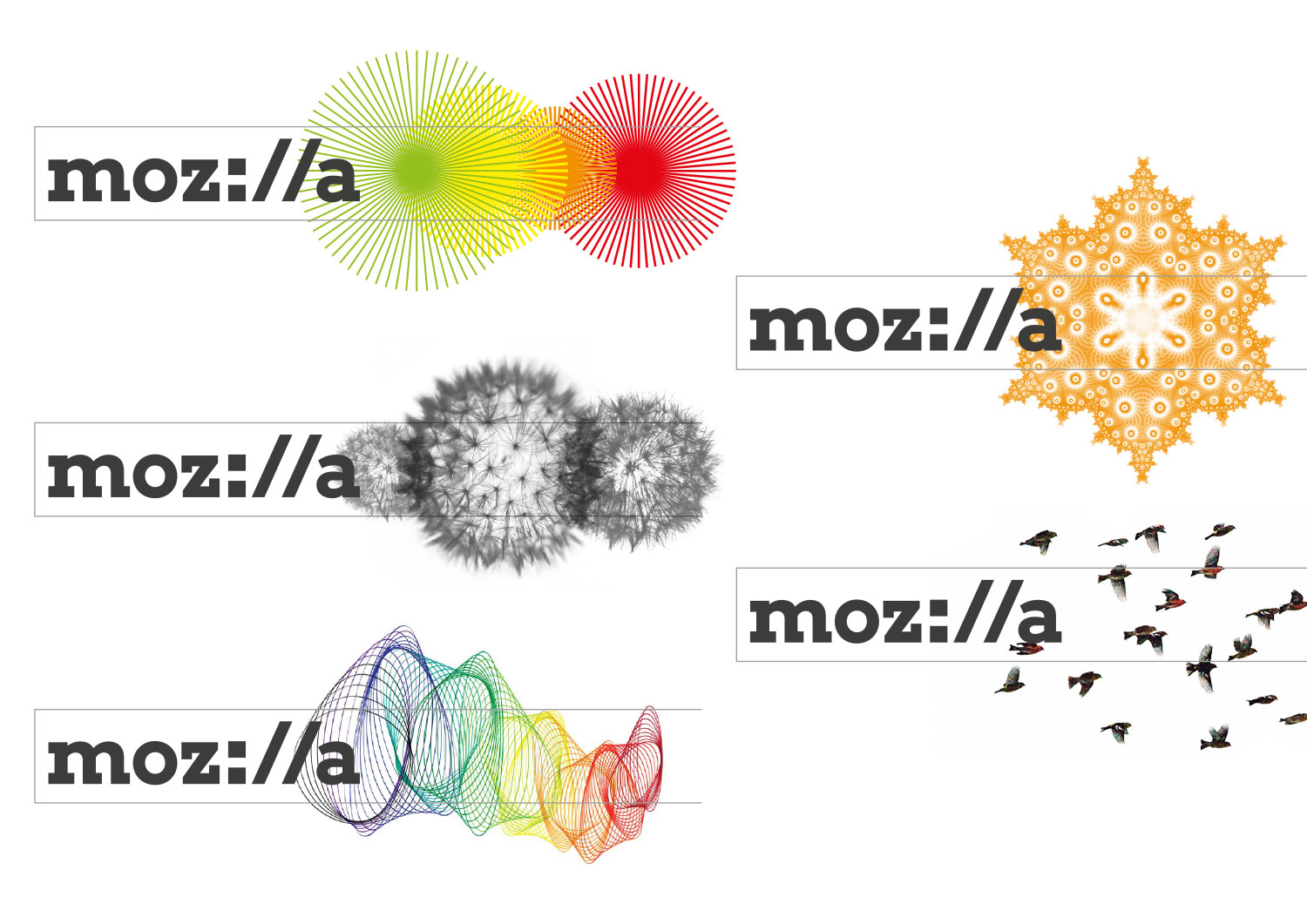

In parallel, an image-led idea had developed, which placed the Mozilla name at the beginning of an imaginary toolbar, and there followed imagery culled directly from the Internet, in an almost haphazard way.

TM: This slide, #19 in the exploratory deck, was the one that really caught our attention. Without losing the ‘moz://a’ idea that coders loved, it added imagery that suggested freedom and exploration which would appeal to a variety of audiences. It was eye-catching. And the thought that this imagery could be ever-changing made me excited by the possibilities for extending our brand as a representation of the wonder of the Internet.

MJ: When we sat back and took stock of this frenetic period of exploration, we realised that we could bring several of these ideas together, and this composite stage was shared with the wider team.

What you see from this, admittedly slightly crude ‘reboot’ of the idea, are the roots of the final route – a dynamic toolkit of words and images, deliberately using bright, neon, early-internet hex colours and crazy collaged imagery. This was really starting to feel like a viable way forward to us.

To be fair, we’d kept Mozilla slightly in the dark for several weeks by this stage. We had retreated to our design ‘bunker’, and weren’t going to come out until we had a reboot of the Protocol idea that we thought was worthy. That took a bit of explaining to the team at Mozilla towers.

TM: That’s a very comic-book image you have of our humble digs, Michael. But you’re right, our almost daily email threads went silent for a few weeks, and we tap-danced a bit back at the office when people asked when we’d see something. It was make or break time from all perspectives. As soon as we saw the new work arrive, we knew we had something great to work with.

MJ: The good news was that, yes, the Mozilla team were on board with the direction of travel. But, certain amends began almost immediately: we’d realised that stand-out of the logo was much improved if it reversed out of a block, and we started to explore softening the edges of the type-forms. And whilst the crazy image collages were, broadly, enjoyed, it was clear that we were going to need some clear rules on how these would be curated and used.

TM: We had the most disagreement over the palette. We found the initial neon palette to be breathtaking and a fun recollection of the early days of the Internet. On the other hand, it didn’t seem practical for use in the user interface for our web properties, especially when these colors were paired together. And our executive team found the neons to be quite polarizing.

MJ: We were asked to explore a more ‘pastel’ palette, that to our eyes lacked some of the ‘oomph’ of the neons. We’d also started to debate the black bounding box, and whether it should or shouldn’t crop the type on the outer edges. We went back and forwards on these details for a while.

TM: To us, it helped to know that the softer colors picked up directly from the highlight bar in Firefox and other browsers. We liked how distinctive the cropped bounding box looked and grew used to it quickly, but ultimately felt that it created too much tension around the logo.

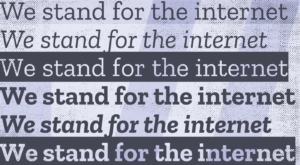

MJ: And as we continued to refine the idea for launch, we also debated the precise typeforms of the logo. In the first stage of the Protocol ‘reboot’ we’d proposed a slab-serif free font called Arvo as the lead font, but as we used it more, we realised many key characters would have to be redrawn.

That started a new search – for a type foundry that could both develop a slab-serif font for Mozilla, and at the same time work on the final letterforms of the logo so there would be harmony between the two. We started discussions with Arvo’s creators, and also with Fontsmith in London, who had helped on some of the crafting of the interim logos and also had some viable typefaces.

TM: Meanwhile a new associate creative director, Yuliya Gorlovetsky, had joined our Mozilla team, and she had distinct ideas about typeface, wordmark, and logo based on her extensive typography experience.

MJ: Finally, after some fairly robust discussions, Typotheque was chosen to do this work, and above and below you can see the journey that the final mark had been on, and the editing process down to the final logo, testing different ways to tackle the key characters, especially the ‘m’, ‘z’ and ‘a’.

This work, in turn, and after many debates about letterspacing, led to the final logo and its set of first applications.

TM: So here we are. Looking back at this makes it seem a fait accompli somehow, even though we faced setbacks and dead-ends along the way. You always got us over the roadblocks though, Michael, even when you disagreed profoundly with some of our decisions.

MJ: Ha! Well, our job was and is to make sure you stay true to your original intent with this brand, which was to be much bolder, more provocative and to reach new audiences. I’ll admit that I sometimes feared that corporate forces or the online hordes were wearing down the distinctive elements of any of the systems we were proposing.

But, even though the iterative process was occasionally tough, I think it’s worked out for the best and it’s gratifying that an idea that was there from the very first design presentation slowly but surely became the final route.

TM: It’s right for Mozilla. Thanks for being on this journey with us, Michael. Where shall we go next?

ray wrote on

Mik wrote on

Suresh Benedy wrote on

Mik wrote on

charlie wrote on

Kim wrote on

Mik wrote on

Teresa wrote on

John Collins wrote on

robin wrote on

Andy wrote on

lizzy wrote on

aj flak wrote on

sharan wrote on

Tim Murray wrote on

DOVANI wrote on

Priyank wrote on

Tim Murray wrote on

Katsza wrote on

Tim Murray wrote on

Dan Wayne wrote on

Ryan Hinchcliff wrote on

Hair-on-FIRE Commonsense Al wrote on

Tim Murray wrote on

Mark Fritch wrote on

Mark Fritch wrote on

gurvinder singh wrote on

Jane wrote on

john Barnes wrote on

Mohit Natani wrote on

Justin wrote on

Scott Richardson wrote on

Krishan wrote on

deggimatt wrote on