The ability to customize and extend Firefox are important parts of Firefox’s value to many users. Extensions are small tools that allow developers and users who install the extensions to modify, customize, and extend the functionality of Firefox. For example, during our workflows research in 2016, we interviewed a participant who was a graduate student in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. While she used Safari as her primary browser for common browsing, she used Firefox specifically for her academic work because of the extension Zotero was the best choice for keeping track of her academic work and citations within the browser. The features offered by Zotero aren’t built into Firefox, but added to Firefox by an independent developer.

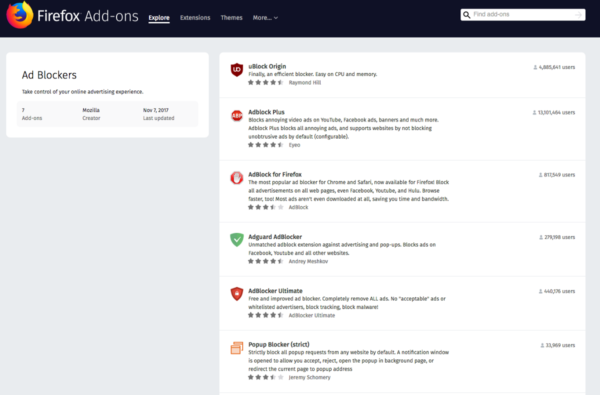

Popular categories of extensions include ad blockers, password managers, and video downloaders. Given the variety of extensions and the benefits to customization they offer, why is it that only 40% of Firefox users have installed at least one extension? Certainly, some portion of Firefox users may be aware of extensions but have no need or desire to install one. However, some users could find value in some extensions but simply may not be aware of the existence of extensions in the first place.

Why not? How can Mozilla facilitate the extension discovery process?

A fundamental assumption about the extension discovery process is that users will learn about extensions through the browser, through word of mouth, or through searching to solve a specific problem. We were interested in setting aside this assumption and to observe the steps participants take and the decisions they make in their journey toward possibly discovering extensions. To this end, the Firefox user research team ran two small qualitative studies to understand better how participants solved a particular problem in the browser that could be solved by installing an extension. Our study helped us understand how participants do — or do not — discover a specific category of extension.

Our Study

Because ad blockers are easily the most popular type of extension in installation volume on Firefox (more generally, some kind of ad blocking is being used on 615 million devices worldwide in 2017), we chose them as an obvious candidate for this study. Their popularity and many users’ perception of some advertising as invasive and distracting is a good mix that we believed could pose a common solvable problem for participants to engage with. (Please do not take our choice of this category of extensions for this study as an official or unofficial endorsement or statement from Mozilla about ad blocking as a user tool.)

In order to understand better how users might discover extensions (and why those chose a particular path), we conducted two small qualitative studies. The first study was conducted in-person in our Portland, Oregon offices with five participants. To gather more data, we conducted a remote, unmoderated study using usertesting.com with nine participants in the US, UK, and Canada. In total, we worked with fourteen participants. These participants used Firefox as their primary web browser and were screened to make certain that they had no previous experience with extensions in Firefox.

In both iterations of the study, we asked participants to complete the following task in Firefox:

Let’s imagine for a moment that you are tired of seeing advertising in Firefox while you are reading a news story online. You feel like ads have become too distracting and you are tired of ads following you around while you visit different sites. You want to figure out a way to make advertisements go away while you browse in Firefox. How would you go about doing that? Show us. Take as much time as you need to reach a solution that you are satisfied with.

Participants fell into roughly two categories: those who installed an ad blocking extension — such as Ad Block Plus or uBlock Origin — and those who did not. The participants who did not install an extension came up with a more diverse set of solutions.

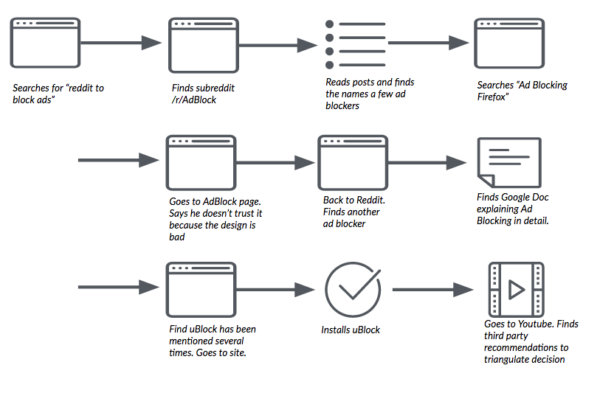

First, among the fourteen participants across the two studies, only six completed the task by discovering an ad blocking extension (two of these did not install the extension for other reasons). The participants who completed the task in this manner all followed a similar path: they searched via a search engine to seek an answer. Most of these participants were not satisfied with accepting only the extensions that were surfaced from search results. Instead, these participants exhibited a high degree of information literacy and used independent reviews to assess and triangulate the quality, reputation, and reliability of the ad blocking extension they selected. More generally, they used the task as an opportunity to build knowledge about online advertising and ad blocking; they looked outside of their familiar tools and information sources.

One participant (who we’ll call “Andrew”) in our first study is a technically savvy user but does not frequently customize the software he uses. When prompted by our task, he said, “I’m going to do what I always do in situations where I don’t know the answer…I’m going to search around for information.” In this case, Andrew recalled that he had heard someone once mention something about blocking ads online and searched for “firefox ad block” in DuckDuckGo. Looking through the search results, he found a review on CNET.com that described various ad blockers, including uBlock Origin. While Andrew says that he “trusts CNET,” he wanted to find a second review source that would provide him with more information. After reading an additional review, he follows a link to the uBlock Firefox extension page, reads the reviews and ratings there (specifically, he is looking for a large number of positive reviews as a proxy for reliability and trustworthiness), and installs the extension. For his final step, Andrew visits two sites (wired.com and huffingtonpost.com) that he believes use a large number of display ads and confirms that the ad blocker is suppressing their display.

The remaining participants did not install an ad blocking extension to complete the task. Unlike the participants who ultimately installed an ad blocking extension, these participants did not use a search engine or an outside information source in order to seek a solution to the task. Instead, they fell back on and looked inside tools and resources with which they were already familiar. Also, unlike the participants who were successful installing an ad blocking extension, these participants typically said they were dissatisfied with their solutions.

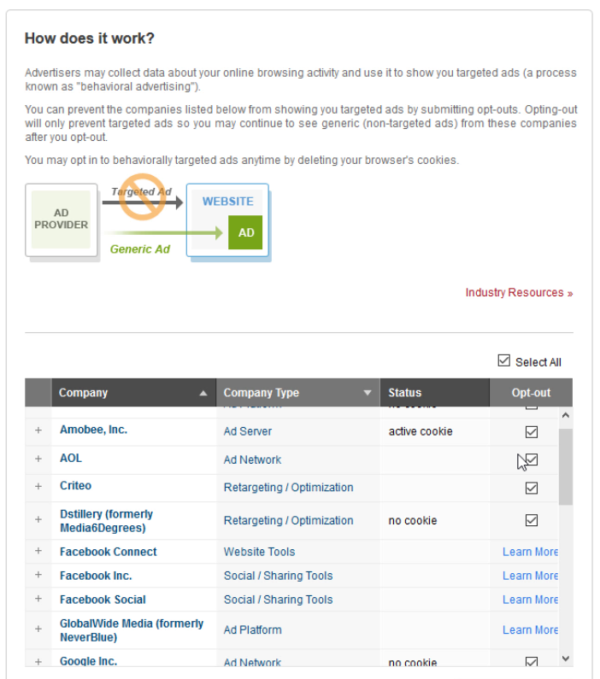

These participants generally followed two main routes to complete the task: they either looked within the browser in Preferences or other menus or they looked into the ads themselves. For the participants who looked in Preferences, many found privacy and security related options, but none related to blocking advertising. These participants did not seek out outside information sources via a search engine and eventually they gave up on the task.

A participant (“Marion”) in our first study recalled that she had seen a link once in an advertisement offering her “Ad Choices.” Ad Choices is a self-regulatory program in North America and the EU that is “aimed to give consumers enhanced transparency and control.” Marion navigated to a site she remembered had display advertising that offered a link to information on the program. She followed the link which took her to a long list of options for opting out of specific advertising themes and networks. Marion selected and deselected the choices she believed were relevant to her. Unfortunately, the confirmations from the various ad networks for her actions either did not work or did not provide much certainty into her actions. She navigated back to the site that she visited previously and could not discern any real difference in display advertising before and after enrolling in the Ad Choices program.

There were some limitations with this research. The task provided to participants is only a single situation that would cue them to seek out an extension to solve a problem. Rather, we imagine a cumulative sense of frustration might prompt users to seek out a solution. We would anticipate that they may hear about ad blocking from word of mouth or a news story (as participants in a similar study run at the same time with participants who were familiar with extensions demonstrated). Also, ad blocking is a specific domain of extension that has its own players and ecosystem. If we asked participants for example to find a solution to managing their passwords, we would expect a different set of solutions.

At a high level, those participants who displayed elements of traditionally defined digital information literacy were successful in discovering extensions to complete the task. This observation emerged through the analysis process in our second study. In future research, it would be useful to include some measurement of participants’ digital literacy or include related tasks to determine the strength of this relationship.

Nevertheless, this study provided us with insight into how users seek out information to discover solutions to problems in their browser. We gathered useful data on users’ mental model of the software discovery process, the information sources they looked to discover new functionality, and finally what kinds of information was important, reliable, and trustworthy. Those participants who did not seek out independent answers, fell back on the tools and information with which they were already familiar; these participants were also less satisfied with their solutions. These results demonstrate a need to provide cues to participants about Extensions within tools they are familiar with already such as Firefox’s Preferences/Options menu. Further, we need to surface cues in other channels (such as search engine results pages) that could lead Firefox users to relevant extensions.

Thanks to Philip Walmsley, Markus Jaritz, and Emanuela Damiani for their participation in this research project. Thanks to Jennifer Davidson and Heather McGaw for proofreading and suggestions.