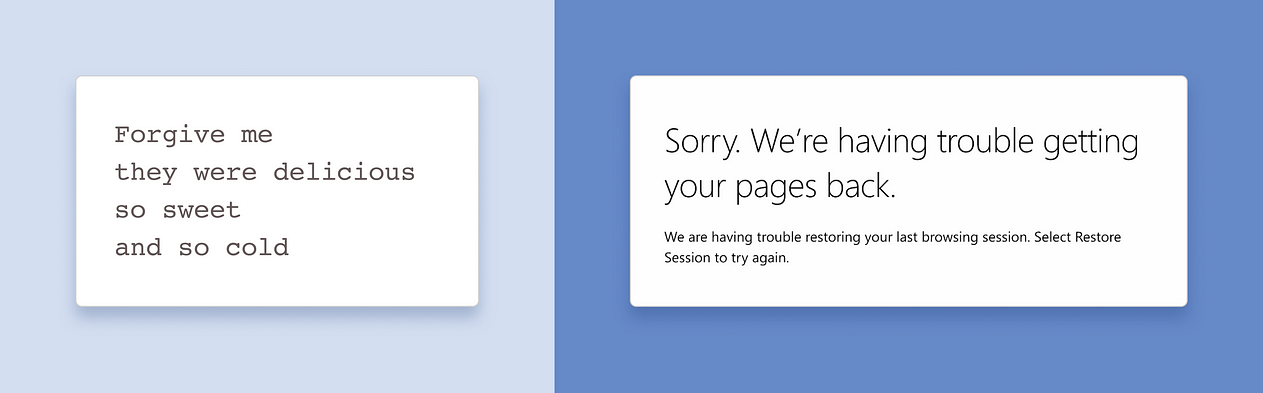

Excerpts: “This Is Just To Say” by William Carlos Williams and a Firefox error message

Word nerds make their way into user experience (UX) writing from a variety of professional backgrounds. Some of the more common inroads are journalism and copywriting. Another, perhaps less expected path is poetry.

I’m a UX content strategist, but I spent many of my academic years studying and writing poetry. As it turns out, those years weren’t just enjoyable — they were useful preparation for designing product copy.

Poetry and product copy wrestle with similar constraints and considerations. They are each often limited to a small amount of space and thus require an especially thoughtful handling of language that results in a particular kind of grace.

While the high art of poetry and the practical, business-oriented work of UX are certainly not synonymous, there are some key parallels to learn from as a practicing content designer.

1. Both consider the human experience closely

Poets look closely at the human experience. We use the details of the personal to communicate a universal truth. And how that truth is communicated — the context, style, and tone — reflect the culture and moment in time. When a poem makes its mark, it hits a collective nerve.

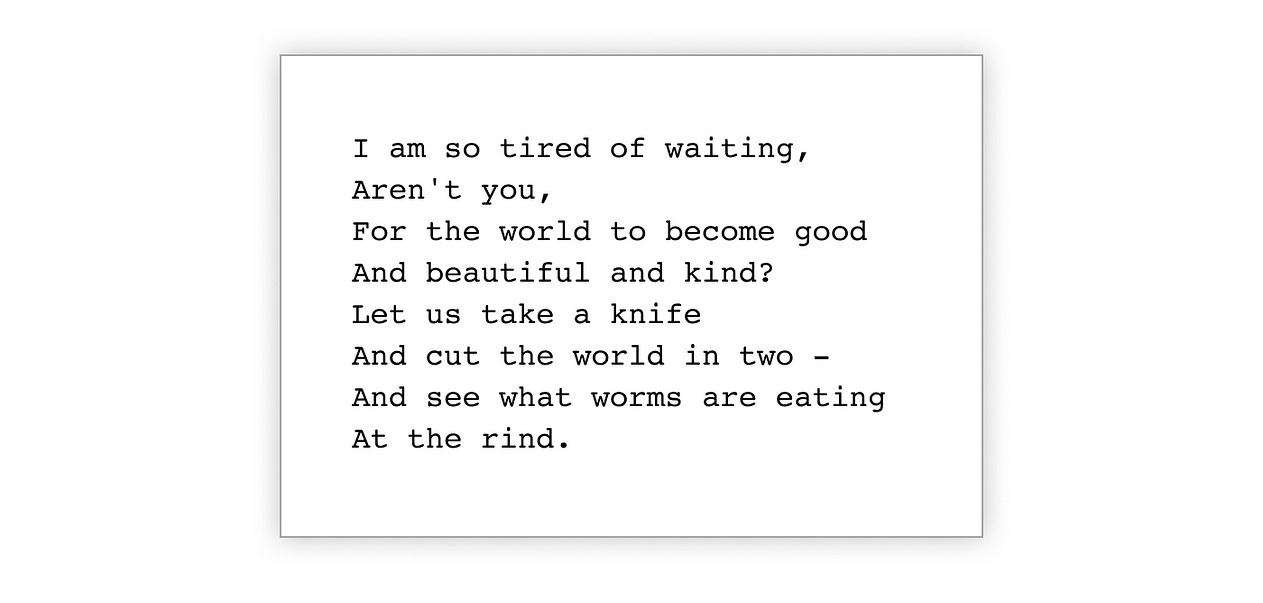

“Tired” by Langston Hughes

Like poetry, product copy looks closely at the human experience, and its language reflects the culture from which it was born. As technology has become omnipresent in our lives, the language of the interface has, in turn, become more conversational. “404 Not Found” messages are (ideally) replaced with plain language. Emojis and Hmms are sprinkled throughout the digital experience, riding the tide of memes and tweets that signify an increasingly informal culture. You can read more about the relationship between technology and communication in Erika Hall’s seminal work, Conversational Design.

While the topic at hand is often considerably less exalted than that of poetry, a UX writer similarly considers the details of a moment in time. Good copy is informed by what the user is experiencing and feeling — the frustration of a failed page load or the success of a saved login — and crafts content sensitive to that context.

Product copy strikes the wrong note when it fails to be empathetic to that moment. For example, it’s unhelpful to use technical jargon or make a clever joke when a user encounters a dead end. This insensitivity is made more acute if the person is using the interface to navigate a stressful life event, like filing for leave when a loved one is ill. What they need in that moment is plain language and clear instructions on a path forward.

2. They make sense of complexity with language

Poetry helps us make sense of complexity through language. We turn to poetry to feel our way through dark times — the loss of a loved one or a major illness — and to commemorate happy times — new love, the beauty of the natural world. Poetry finds the words to help us understand an experience and (hopefully) move forward.

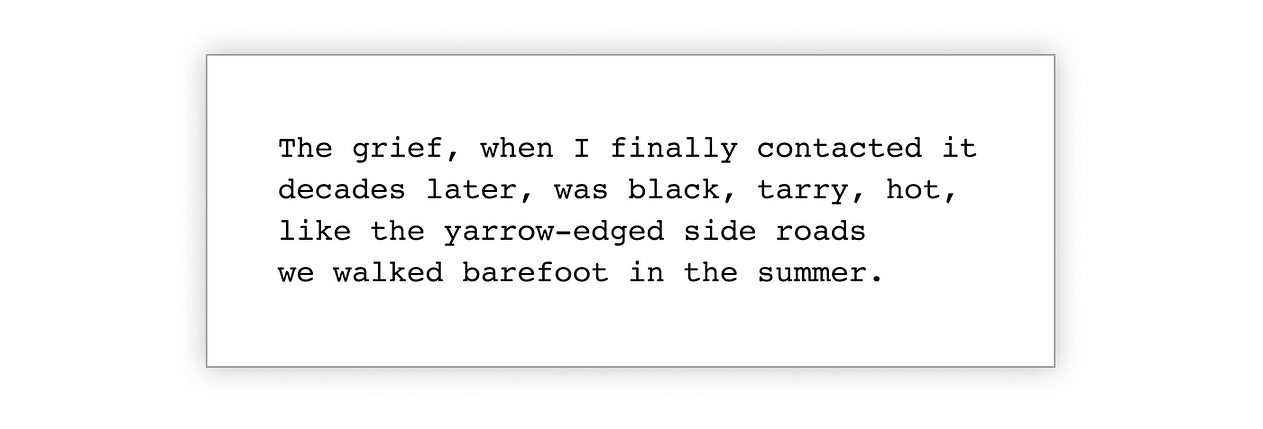

Excerpt: “Toad” by Diane Seuss

UX writers also use the building blocks of language to help a user move forward and through an experience. UX writing requires a variety of skills, including the ability to ask good questions, to listen well, to collaborate, and to conduct research. The foundational skill, however, is using language to bring clarity to an experience. Words are the material UX writers use to co-create experiences with designers, researchers, and developers.

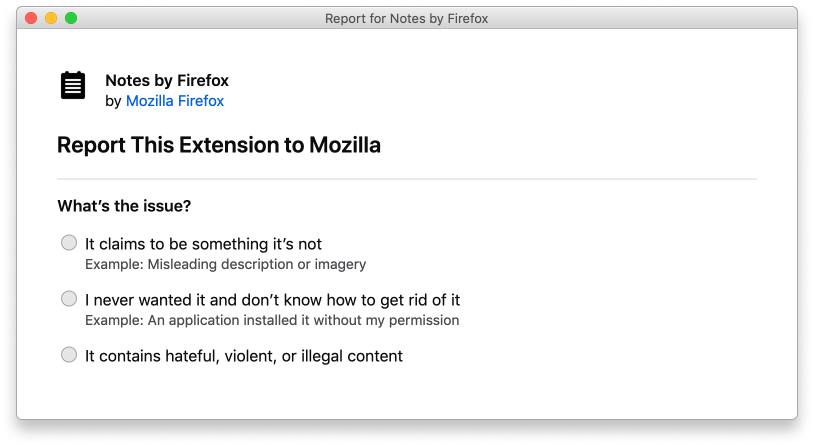

Excerpt of a screen for Firefox users to report an issue with a browser extension. The flow enables the user to report an extension, troubleshoot issues, and remove the extension. Co-created with designer Philip Walmsley.

3. Words are selected carefully within a small canvas

“Poetry is your best source of deliberate intentional language that has nothing to do with your actual work. Reading it will descale your mind, like vinegar in a coffee maker.” — Conversational Design, Erika Hall

Poetry considers word choice carefully. And, while poetry takes many forms and lengths, its hallmark is brevity. Unlike a novel, a poem can begin and end on one page, or even a few words. The poet often uses language to get the reader to pause and reflect.

Product copy should help users complete tasks. Clarity trumps conciseness, but we often find that fewer words — or no words at all — are what the user needs to get things done. While we will include additional language and actions to add friction to an experience when necessary, our goal in UX writing is often to get out of the user’s way. In this way, while poetry has a slowing function, product copy can have a streamlining function.

Working within these constraints requires UX writers to also consider each word very carefully. A button that says “Okay!” can mean something very different, and has a different tone, than a button that says, “Submit.” Seemingly subtle changes in word choice or phrasing can have a big impact, as they do in poetry.

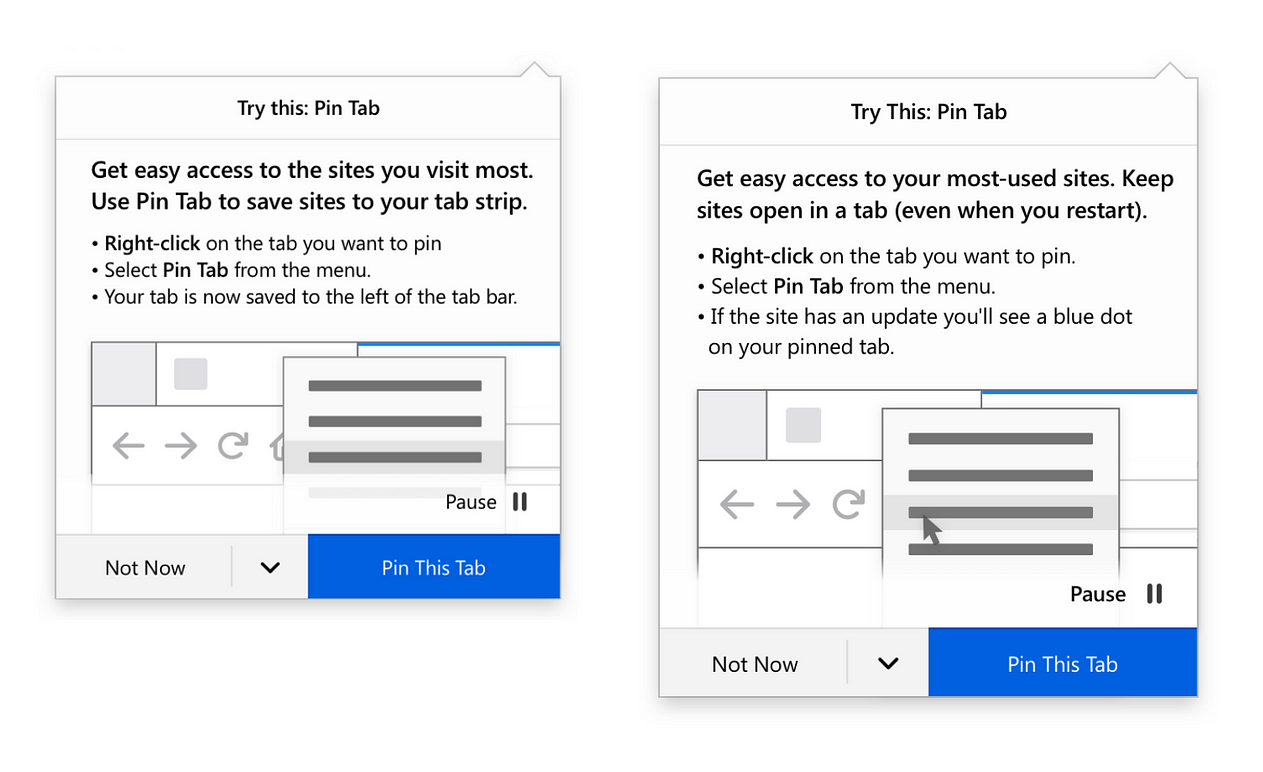

Left: Early draft of a recommendation panel for the Firefox Pin Tab feature. Right: final copy, which does not include the descriptors “tap strip” or “tab bar” because users might not be familiar with these terms. A small copy change like using “open in a tab” instead of “tab strip” can have a big impact on user comprehension. Co-created with designer Amy Lee.

4. Moment and movement

Reading a poem can feel like you are walking into the middle of a conversation. And you have — the poet invites you to reflect on a moment in time, a feeling, a place. And yet, even as you pause, poetry has a sense of moment — metaphor and imagery connect and build quickly in a small amount of space. You tumble over one line break on to the next.

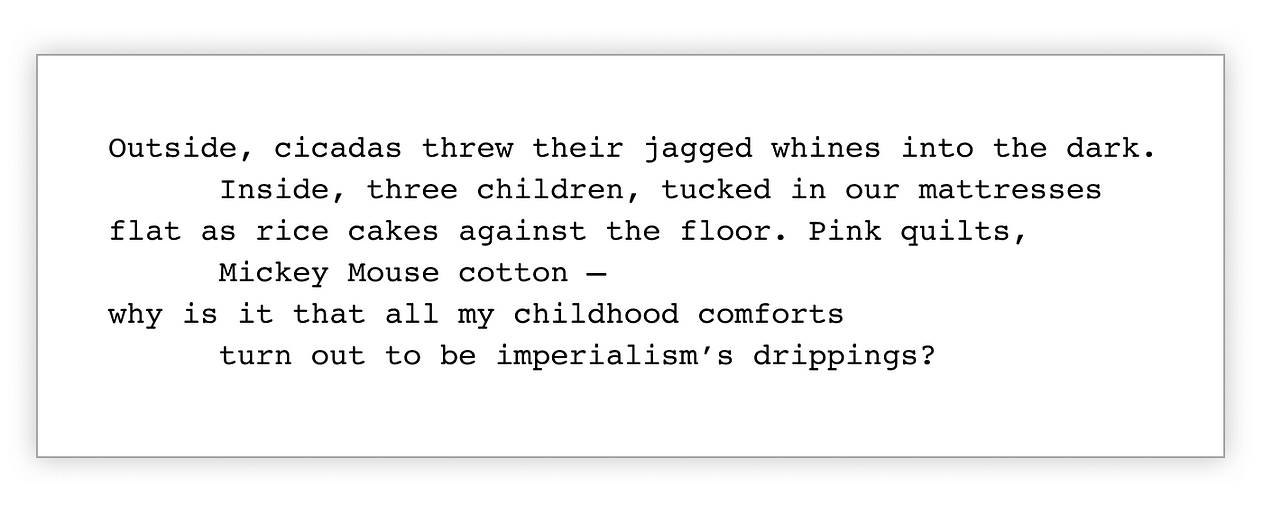

Excerpt: “Bedtime Story” by Franny Choi

Product copy captures a series of moments in time. But, rather than walking into a conversation, you are initiating it and participating in it. One of the hallmarks of product copy, in contrast to other types of professional writing, is its movement — you aren’t writing for a billboard, but for an interface that is responsive and conditional.

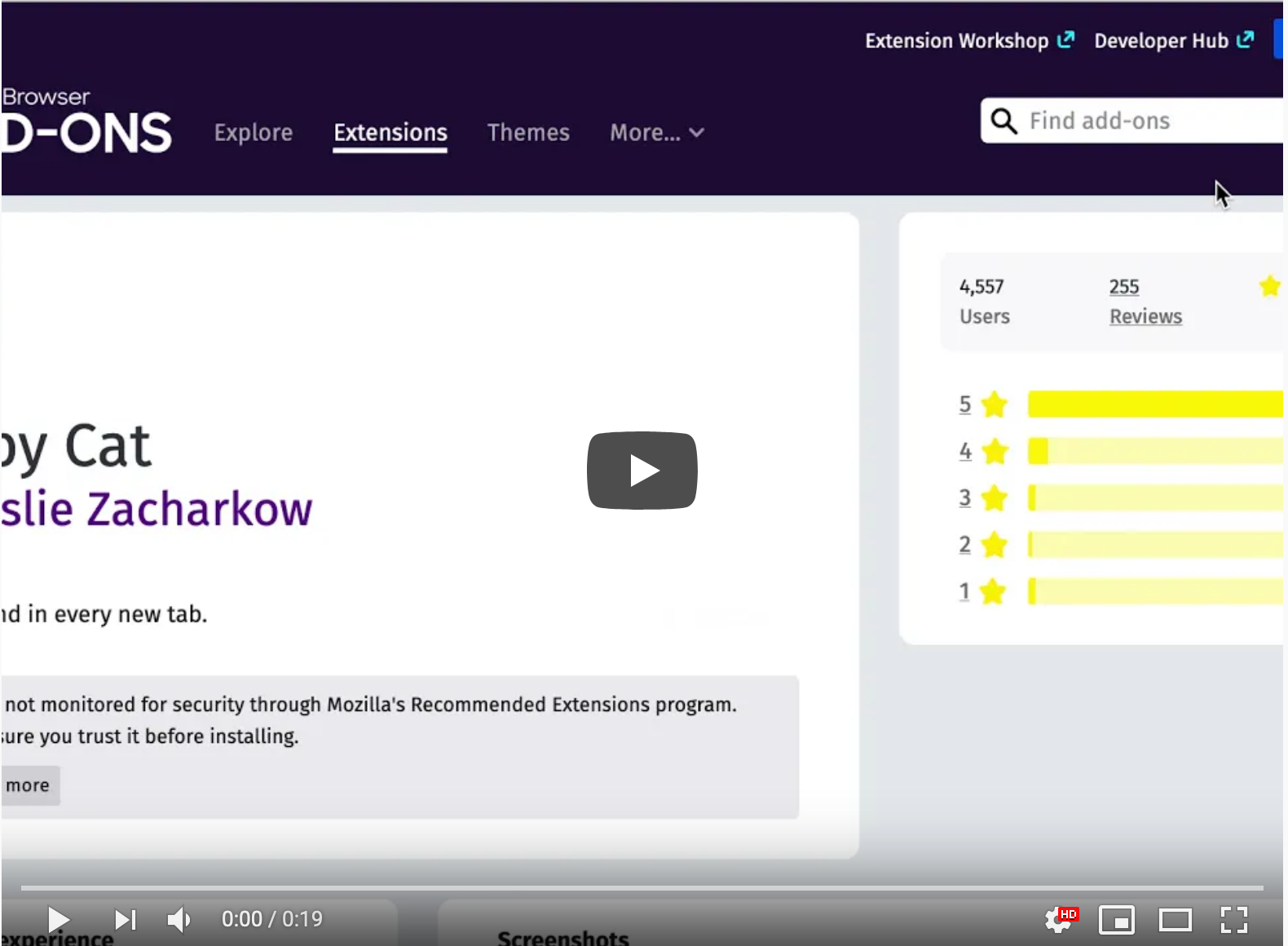

The installation flow for the browser extension, Tabby Cat, demonstrates the changing nature of UX copy. Co-created with designer Emanuela Damiani.

5. Form is considered

Poetry communicates through language, but also through visual presentation. Unlike a novel, where words can run from page to page like water, a poet conducts flow more tightly in its physical space. Line breaks are chosen with intention. A poem can sit squat, crisp and contained as a haiku, or expand like Allen Ginsburg’s Howl across the page, mirroring the wild discontent of the counterculture movement it captures.

Product copy is also conscious of space, and uses it to communicate a message. We parse and prioritize UX copy into headers and subheadings. We chunk explanatory content into paragraphs and bullet points to make the content more consumable.

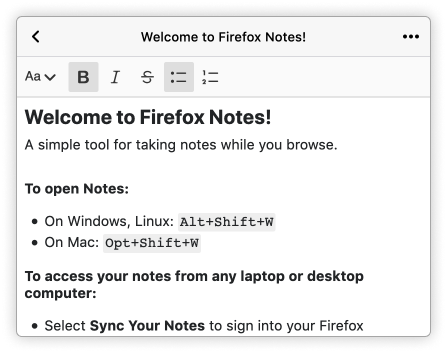

The introductory note for the Firefox Notes extension uses type size, bold text, and bullet points to organize the instructions and increase scannability.

6. Meaning can trump grammar

Poetry often plays with the rules of grammar. Words can be untethered from sentences, floating off across the page. Sentences are uncontained with no periods, frequently enjambed.

Excerpt: “[i carry your heart with me(i carry it in]” by E. E. Cummings

In product writing, we also play with grammar. We assign different rules to text elements for purposes of clarity — for example, allowing fragments for form labels and radio buttons. While poetry employs these devices to make meaning, product writing bends or breaks grammar rules so content doesn’t get in the way of meaning — excessive punctuation and title case can slow a reader down, for example.

“While mechanics and sentence structure are important, it’s more important that your writing is clear, helpful, and appropriate for each situation.” — Michael Metts and Andy Welfle, Writing is Designing

Closing thoughts, topped with truffle foam

While people come to this growing profession from different fields, there’s no “right” one that makes you a good UX writer.

As we continue to define and professionalize the practice, it’s useful to reflect on what we can incorporate from our origin fields. In the case of poetry, key points are constraint and consideration. Both poet and product writer often have a small amount of space to move the audience — emotionally, as is the case for poetry, and literally as is the case for product copy.

If we consider the metaphor of baking, a novel would be more like a Thanksgiving meal. You have many hours and dishes to choreograph an experience. Many opportunities to get something wrong or right. A poem, and a piece of product copy, have just one chance to make an impression and do their work.

In this way, poetry and product copy are more like a single scallop served at a Michelin restaurant — but one that has been marinated in carefully chosen spices, and artfully arranged with a puff of lemon truffle foam and Timut pepper reduction. Each element in this tiny concert of flavors carefully, painstakingly composed.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Michelle Heubusch and Betsy Mikel for your review.